After the most recent sale of two vintage Panerai watches at the renowned auction house Artcurial in Paris, vintage watch enthusiasts around the globe keep asking the same question. Is vintage Panerai back in the game?

Here’s what happened: Both watches fetched prices that reminded of the glorious days of vintage Panerai collecting, before a certain Jose Pereztroika came along and started calling out fakes and made-up watches.

Lot 79, a 3646 “Kampfschwimmer” without any special engravings, reached the impressive sum of EUR 84,500.00.

Lot 116, the super elusive 6152 with great provenance fetched mind-boggling EUR 226,000.00. That’s almost double the high estimate. The story of the original owner of this watch expands from the very beginnings of the original Decima Flottiglia MAS to the reorganization process of the assault units after WW2. And of course, all this is deeply interwoven with the history of G. Panerai e Figlio.

LOT 116 – Rolex Radiomir Panerai Ref. 6152 beloging to Amedeo Vesco

Reference: Rolex 6152

Dial: Radiomir Panerai (1950s)

Case number: 956638

Estimate: EUR 80,000 – 120,000

Realized price: EUR 226,000

Reference 6152 – not to be confused with the more common later Ref. 6152/1 – is one of the rarest vintage Rolex-Panerai models ever made. Ref. 6152 was the first Rolex-made Panerai watch model produced after World War 2. Only seven examples have surfaced so far, plus 5 orphaned case backs which were found on Ref. 6152/1 watches.

The present watch belonged to Rear Admiral Amedeo Vesco (1914 -2002), who was one of the key figur of the original Decima Flottiglia MAS. Vesco took part in two operations against the British Naval Base in Gibraltar and was awarded the Silver Medal of Military Valour, not once but twice.

Vesco’s watch entered the market in June 2008, when it was sold by his son together with copies of some of Vesco’s military awards and a letter of authenticity. The picture below from around 1940, shows Amedo Vesco (arrow) surrounded by famous comrades in Bocca di Serchio.

In the early 1950s, Vesco was appointed Commander of the Italian post war assault units. He was probaly one of the first to receive the new post war watch.

I found the following footage from the 1950s. From 5:55 onwards, you can see a guy in camouflage uniform, between the two men in white, who is wearing a Panerai watch. I believe you are looking at Amedeo Vesco wearing his Panerai Reference 6152! Check it out!

.

Ref. 6152 featured an upgraded version of the iconic Panerai aluminium sandwich dials known from WW2. For Ref. 6152, Panerai found a way to make them considerably thinner.

At first glance, the dial of Vesco’s 6152 looks as if it was repainted, but that is not the case. Panerai filled the cut-outs for numerals and markers with a transparent substance which became brittle of the years. This phenomenon can be found on other 6152s as well.

An interesting observation is how intricate the shape of the orginal hands is. From far, they seem to be made from a flat sheet of metal but a closer looks reveals they are actually quite artfully finished. Art Deco right down to the last detail!

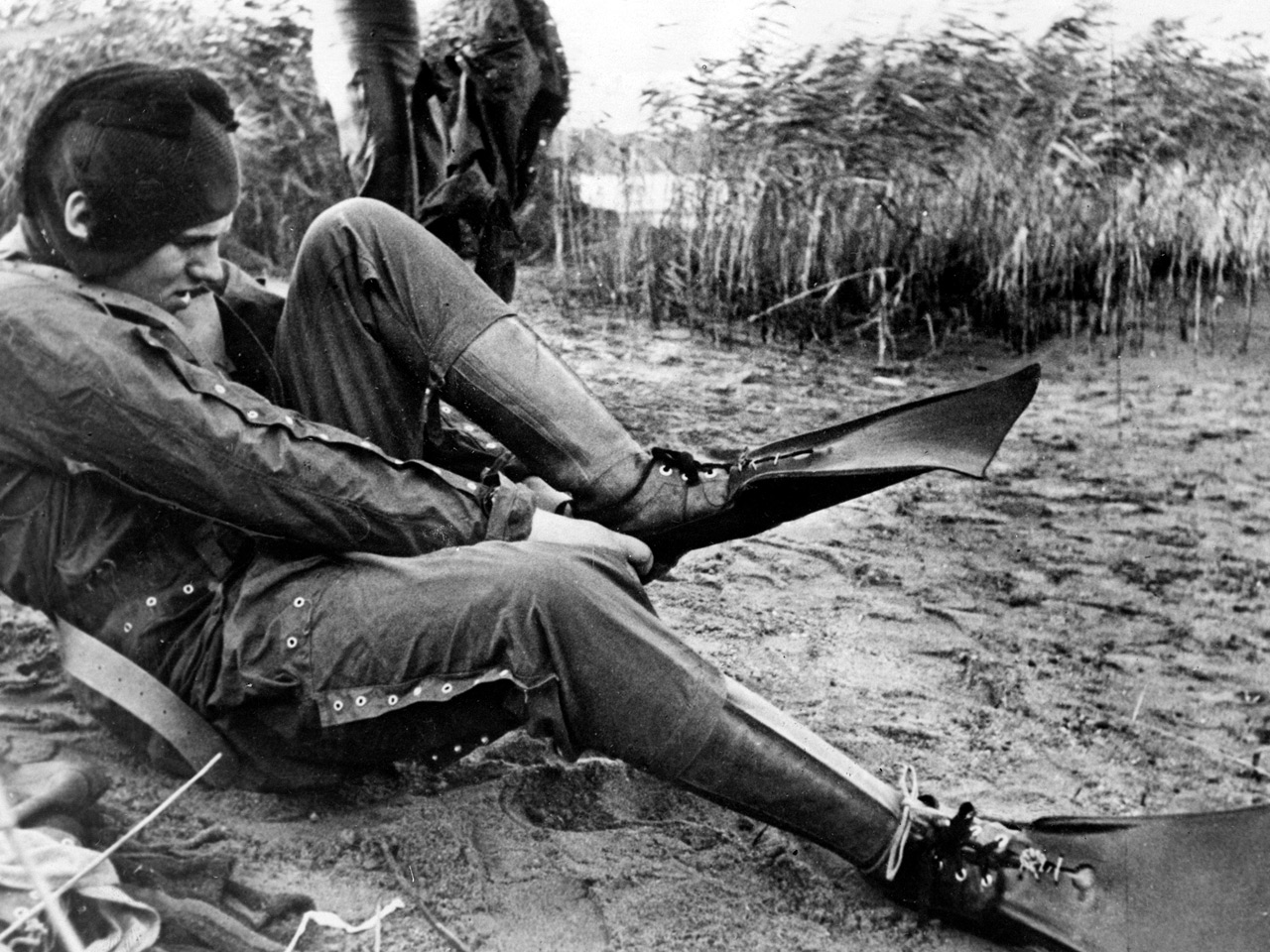

Amedeo Vesco, the original owner of this watch, was among the first divers to train the handling of the famous manned torpedoes named “Siluro a lenta corsa” (SLC) aka Maiale at the secret training facility of Bocca di Serchio in the late 1930s.

Together with guys like Teseo Tesei (inventor of the SLC), Gino Birindelli and Luigi Durand de la Penne, Vesco developed and optimized attack procedures under real life conditions on the Serchio River. The drawing below depicts the support vessel on which the Maiales were maintained and kept away from curious eyes under a tarp.

The next picture was most certainly taken on the support vessel mentioned above. Can you see the tarp above the guy’s head?

Vesco must a been an excellent diver as in Sept. 1940, when the Italian Royal Navy established the first official diver school in the premises of the Naval Academy “San Leopoldo” in Livorno under the lead of Captain Ernesto Forza, Vesco was appointed head of diving courses.

.

Operation B.G.3 – Total failure

In May 1941, Amedeo Vesco’s skills were tested for the first time. He was part of B.G.3, a secret Decima MAS operation to attack the British fleet in the heavily fortified British Naval Base of Gibraltar. After B.G.2, a failed attack on Gibraltar where Gino Birindelli and parts of his SLC had been captured, the Decima MAS sent a new squad into action.

With Gibraltar, the British controlled the strategically important passage between Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. This situation was unbearable for the Italians as it confined the Italian Navy to the Mediterranean Sea. During WW2, the civilian population of Gibraltar was evacuated and the “Rock”, as many used to call it, was strenghtened as a fortress. Gibraltar lies in the south of Spain. It was captured from Spain by Anglo-Dutch forces in 1704 and ceded to Great Britain in 1713.

B.G.3 was a redesigned operation compared to B.G.2. To avoid the long and exhausting submarine journey of previous missions, Vesco and seven fellow frogmen were brought to Spain undercover by airplane. Arrived in Spain, the men were received by agents and taken to Cádiz, where the Italians had established a secret submarine support base (Base C) on a merchant ship named Fulgor.

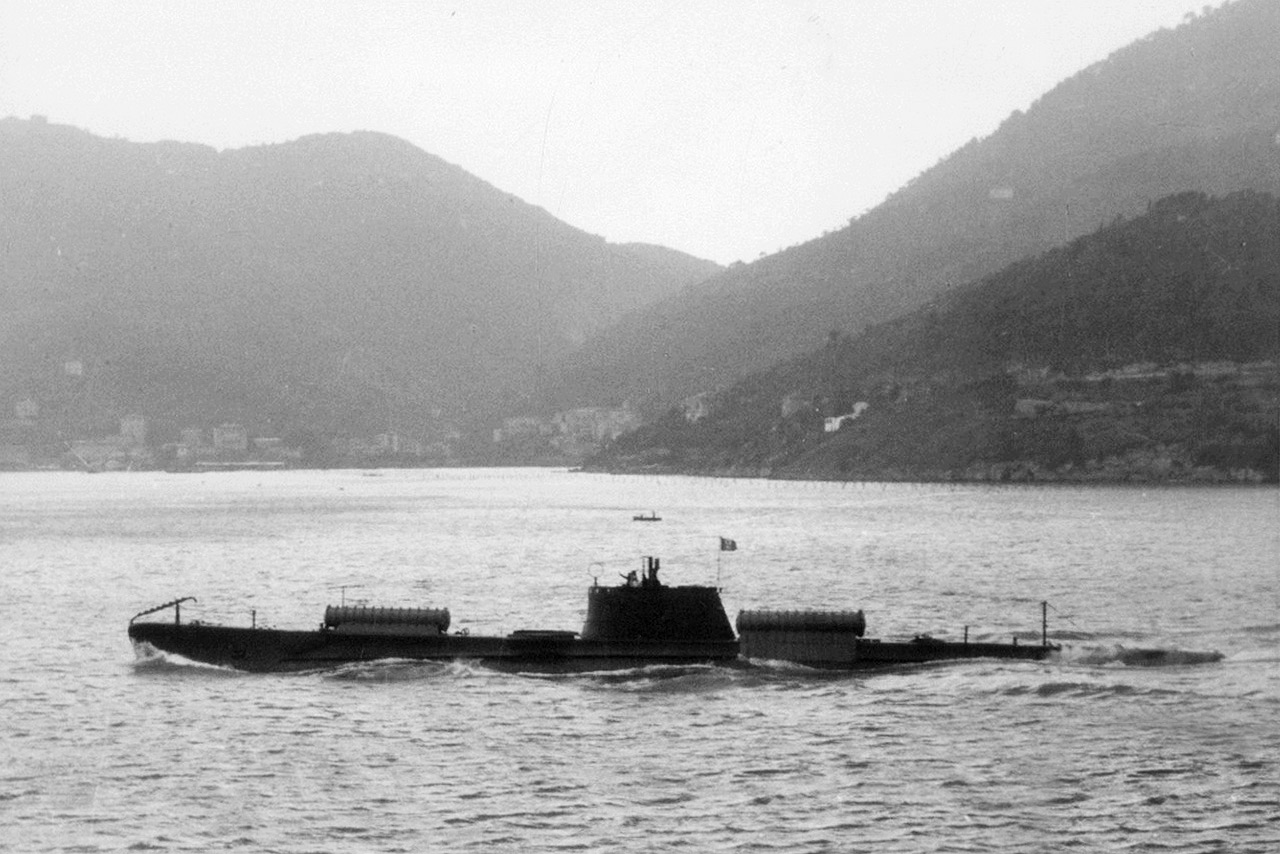

The SLCs were shipped to their destination in cylindrical containers attached to the ouside of the submarine Scire, who’s commander Junio Valerio Borghese had become very experienced in these waters.

Cádiz is located on the Atlantic side of the Strait of Gibraltar and to reach it, Junio Valerio Borghese was required to perform a risky manouver. Passing the Strait undected, despite the presence of the British fleet, who was in full alert due to a previous failed attack.

The Scirè arrived in Cádiz on May 24 but had to stay submerged for the rest of the day at a depth of 40 meteres to avoid detection. Around midnight, the submarine entered the harbour and moored alongside the “Fulgor” where it was resupplied.

A few hours later, Vesco was heading to his first mission. On its way to Algeciras Bay (Bay of Gibraltar), the “Scirè” escaped a British destroyer and had to fight against heavy currents. Once arrived, Borghese thought it would be prudent to wait 24 hours before releasing the SLCs. During this time, the mighty British naval formation known as “Force H” departed from the Naval Base and left the Italian with no major targets. Supermarina, the Headquarters of the Regia Marina in Rome, ordered to attack Allied transport vessels in the Algeciras Bay instead. On May 26 at midnight, Borgehese deployed the Maiales. The “Scirè” sailed back to Italy and the six frogmen were now on their own.

The three crews consisted of Lieutenant Amedeo Vesco with Lieutenant Antonio Marceglia, Lieutenant Decio Catalano with diver Giuseppe Giannoni and Licio Visintini with diver Giovanni Magro.

Vesco’s Maiale broke down right at the beginning of the mission. To preserve their ability to attack three targets, Vesco and his co-pilot tranferred the explosive warhead to Visintini’s Maiale. Then, in order to erase any trace, they sunk the defective craft in deep water. Vesco took seat on Visintini’s SLC, while his co-pilot Marceglia was carried by Catalano.

Further ahead, Catalano chose a transport ship as a suitable target. While the crew was trying to attach the warhead under the hull, Marceglia passed out due to a malfunction of this rebreather. Catalano and Giannoni were able to help him but they lost control of their Maiale in the process. The craft sunk to a depth where it could not be retrieved. Left with no options, the three men swam to shore and destroyed their equipment.

Visintini, Magro and Vesco decided to destroy a tanker, after dismissing three other options. One was a hospital ship, the other sailing under Swiss flag (neutral) and the third just to small to attack. In the process of attaching the warhead to the chosen target, Magro passed out. Visintini and Vesco were able to rescue him but their SLC sunk to the bottom as well and was lost. All three frogmen were able to reach the coast and destroy their equipment.

An agent waiting for the six men at the beach arranged their trip back to Italy where all six SLC pilots were awarded the Silver Medal of Military Valour.

B.G.3 was a total fiasco. The failure was in fact so completely, the British didn’t even realize they had been attacked and as the only positive result for the Italians, the defenses were not increased. Vesco and his comrades would soon get another chance to demonstrate the effectiveness of Maiales.

Reference: The Black Prince and the Sea Devils – The Story of Junio Valerio Borghese and the Elite Units of the Decima MAS, p. 74/75

.

Operation B.G.4 – First success

A few months later, in Sept. 1941, the Decima MAS attempted a new attack on Gibraltar. The previous attack had remained undetected and the element of surprise would still be on their side.

As in Operation B.G.3, the frogmen were again flown to Spain and boarded the “Scirè” in Cadiz in order to sail to Gibraltar. The teams were basically the same as in B.G.3 but this time, Vesco’s co-pilot was Antonio Zozzoli.

On the way to Algeciras Bay, the “Scirè” passed a convoy escorted by British destroyers but remained undetected. On the night of September 19, 1941, the “Scirè” entered the Algeciras Bay and a few hours later, three SLCs were launched near the mouth of the river Guadarranque. Borghese turned his vessel and sailed back to La Spezia.

The three SLC crews consisted of Lieutenant Amedeo Vesco with Lieutenant Antonio Zozzoli, Lieutenant Decio Catalano with Giuseppe Giannoni and Licio Visintini with Giovanni Magro.

.

SLC 210 – Vesco and Zozzoli

What could be better than hearing of Vesco’s mission from himself? The following are excerpts from Amedeo Vesco’s personal report.

“At about 0030 hours on the 20th September 1941, in accordance with Commanding Officer Borghese’s orders, I left the submariner, followed by my number two, Petty Officer Antonio Zozzoli. The target assigned to me was a battleship of the Nelson class, moored inside the harbour, halfway along the south breakwater. The surface approach was normal, though impeded by windes and high seas. I removed my mask at intervals, so as to see with the naked eye, but on each occasion only for a few seconds, because, even when I was stationary, the waves breaking over my face were a great nuisance, especially to my eyes. After an emergency submersion to evade discovery by a patrol boat on duty, I sighted the entrance to the harbour.

I was about 300 meters from the defences and slowed down so as to prevent from being heard by hydrophones and in order to have time to find out about the maneuvers of a boat which was shuttling, with her lights on, in front of the entrance. I set a bee-line course and submerged to the greatest possible depth, proceeding at low speed to prevent the phosphorescence of my wake from being detected from the surface.

At about 0315, I got down to a depth of about 26 meters, just grazing the bottom, which was hard and smooth, and did not interfere in any way with my progress. At about 0330, at a depth of 15 meters, I heard and felt against the cask of the Maiale and against my own body three consecutive underwater explosions. As everything continued to function normally, I decided to go on. At 0340, I was at a depth of 13 meters when I heard two further explosions, slightly more subdued than the previous ones, but of greater volume.”

.

After the first attacks, the British began to systematically use depth charges to prevent enemy divers from entering their naval bases. Vesco realized it would be suicidal to try and penetrate the military harbour under these circumstances and decided to try their luck in the less protected, commercial harbour instead.

“At 0400, I started to look for the most important target. A boat with its lights dimmed was moving about among the steamers. At last, I sighted a vessel with a long, slender outline, lying low in the water and therefore heavily laden; I guessed it to be about 3 or 4 thousand tons displacement. I made my approach beneath the ship, stopped and came up, exhausting the tanks, till I reached the hull. I managed to to this unseen and unheard, but owning to damage to my breathing apparatus, I could not avoid swallowing water containing soda lime which caused burning to my mouth and throat.”

.

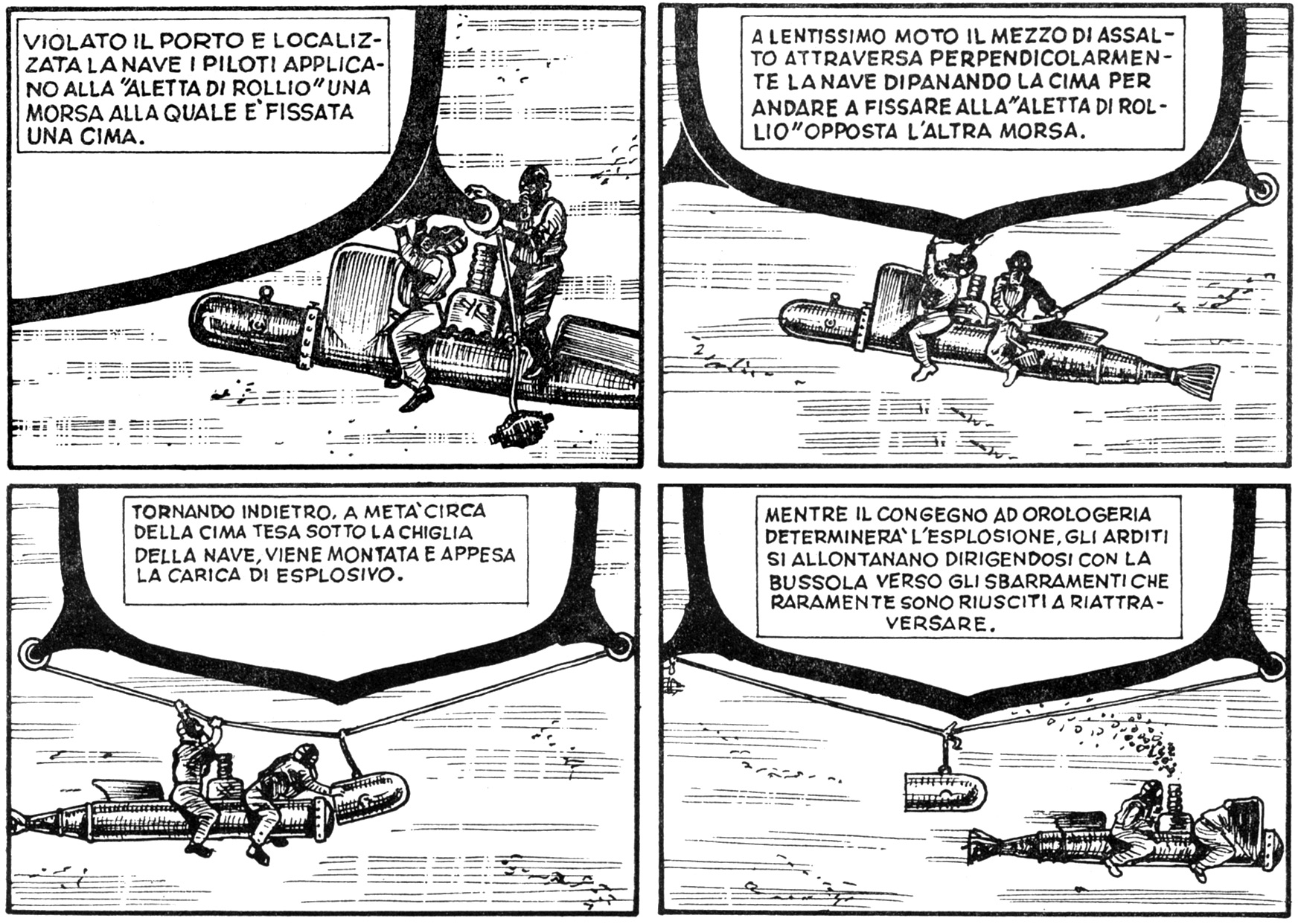

Vesco replaced his defective rebreather with a spare one carried in the SLC and immediately proceeded with his task. Once under the hull, Zozzoli detached the explosive warhead from the SLC and fastened it to the steel cable attached to the tanker Fiona Shell. After setting the timer, both men sneaked away towards the Spanish shore with their SLC.

The picture below illustrates how these attacks were carried out.

Once the beach was in sight, Vesco activated the self-destruct mechanism and let his Maiale disappear in the deep. Around 0700 hours, they got ashore, just 200m meters from the meeting point. Two Spanish sentries spotted them at the beach and shot in the air to halt them. Vesco and Zozzoli had just time to hid their equipment before being arrested and brought to the police station

“We had a good deal of trouble owning to our bad physical condition of the sea, which repeatedly broke over our heads. My second man was very tired and feeling ill. We got ashore just before 0700, about 200 meters west of the prearranged point, where we were halted by two Spanish sentries. One of them instantly fired two rifle-shots into the air. We had just time to hide our two breathing sets in a secluded spot of the beach, as, for obvious reasons, I did not want the sentries to see them. I told the Spaniards we were shipwrecked Italians … We were taken to the coastguard station, where we were met by the agent P., who took steps to recover our breathing sets.”

.

From the station, Vesco and Zozzoli witnessed the punctual explosion of their charge.

“The vessel split in two, slightly astern of the funnel. Her stern disappeared, the bows rising high out of the water.”

.

The two other teams encoutered similar difficulties.

SLC 120 – Catalano and Giannoni

Aware of the risk posed by constant detonations of depth charges and suddenly followed by a silent patrol boat he first had to shake off, Catalano decided to attack an Allied merchant ship in the less guarded commercial harbour. After attaching the warhead to a large tanker, Catalano realized the vessel was Italian, the “Pollenzo” from Genoa. Although it was a captured ship, Catalano and his second man Giannoni detached the war head and opted for a large British merchant ship named “Durham” instead. At 0516 they set the timer and left the scene. Catalano sank his Maiale after activating the self-destruct device. Both men swan ashore while destroying their breathing apparatuses.

At 0916, the charge attached to the “Durham” exploded and the ship settled on the seabed by stern. Four powerful tugboats were immediately sent to tow the “Durham” ashore.

.

SLC 220 – Visintini and Magro

Visintini and Magro were the only ones to succeed in entering the military harbour. They were able to overcome the obstructions at the entrance but in doing so, they lost too much time. Only two hours before dawn. Their prearranged target, the aircraft carrier “HMS Ark Royal” was too far way. Visintini spotted a large cruiser closeby but due to continous explosions of depth charges near the vessel, he decided to attack the tanker “Denbydale” instead, hoping the explosion would cause fires to break out on nearby ships as well. At 0440, they set the timer and managed to leave the military harbour undetected. They sank their craft and reached the shore at 0630, where agent P. was already expecting them. At 0843, the charge under the “Denbydale” exploded but the expected petrol blaze did not occur as the British were using high density oil that did not easily ignite. The “Denbydale” was seriously damaged but remained afloat.

.

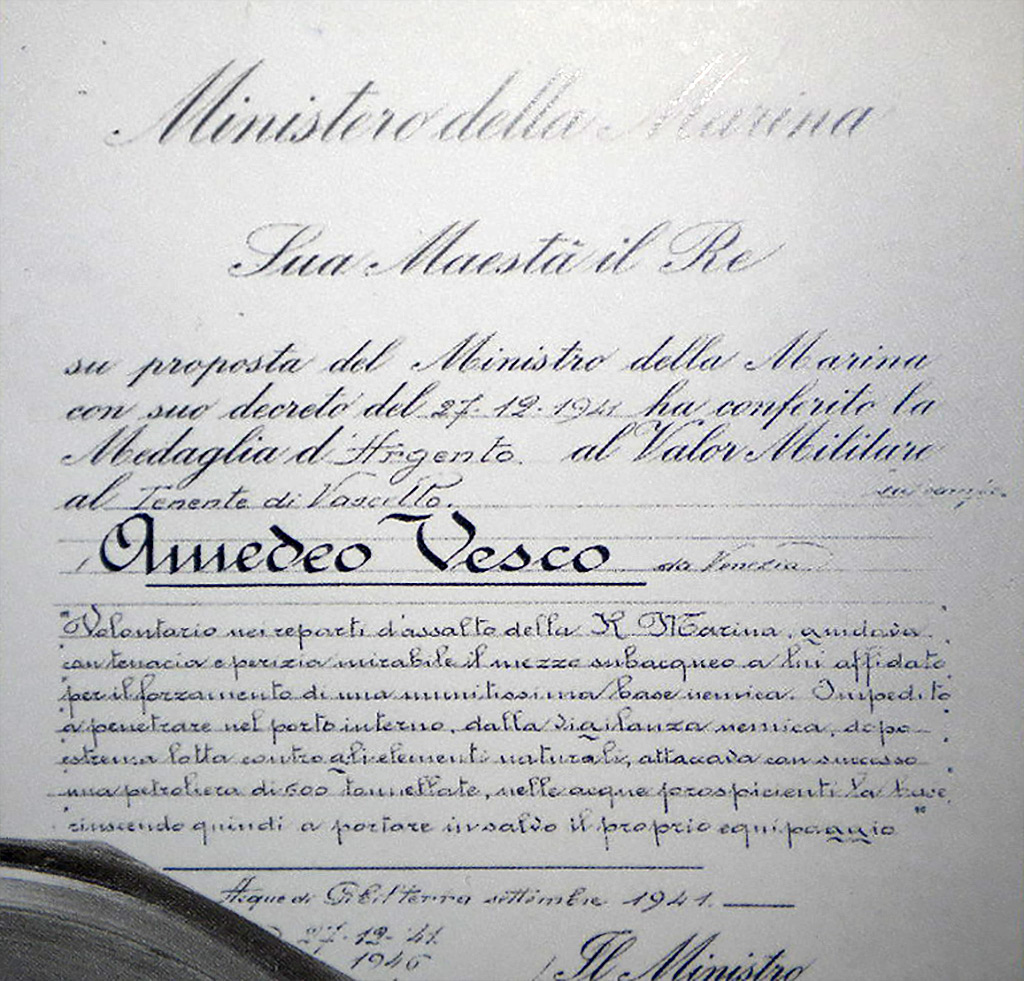

Operation B.G.4 was the first important success for the Maiales and proved their effectiveness. All six frogmen returned safely to Italy where they were awarded the Silver Medal of Military Valour. Borghese was promoted to Commander.

The following picture shows Vesco’s award ertificate for the ‘Silver Medal of Military Valour’ (M.A.V.M.) optained in Sept. 1941.

References: The Black Prince and the Sea Devils – The Story of Junio Valerio Borghese and the Elite Units of the Decima MAS / Submariner: An anthology of firsthand accounts of the war under the sea, 1939 – 1945 / Decima Flottiglia MAS: The Best Commandos of the Second World War / The Royal Navy and the Mediterranean: Vol. 2: Novemenber 1940 – December 1941

.

Armistice of Cassibile – Italy surrendered to the Allies

In May 1943, Borghese replaced Ernesto Forza as Commander of the Decima Flottiglia MAS. Two months later, in July 1943, the Allies landed in Sicily and soon started bombing the city of Rome. The Italian population grew weary of the war and on Aug. 25, 1943, Mussolini was arrested on the Italian king’s orders. In early Sept. 1943, Italy officialy surrendered to the Allies without giving specific orders to the armed forces.

Germany, the former ally, saw this as a treasonous act and immediately occupied large parts of Italy. Italian soldiers were rounded up. They had to hand over their arms and choose between keep fighting with Germany or be deported for slave labour. Around 30,000 Italian soldiers were killed for not surrendering their arms. Another 700,000 were sent to Germany for slave labour, where ten thousands of them died.

Parts of the Decima MAS under the command of Junio Valerio Borghese remained loyal to the Nazis. Borghese, left with no specific orders, opted to stay under arms to retain some sort of control over the chaotic situation. His men were free to leave though and many left. Under Borghese’s lead, the Decima Flottiglia MAS was reorganized and mutated to a politically motivated infantry division under German command. The unit was mostly deployed against Italian partisans and communists.

Other Decima MAS members remained loyal to the king and fought alongside the Allies against the Nazis. These men formed, together with British divers, the unit known as “MARIASSALTO” under the lead of Captain Ernesto Forza.

Amedeo Vesco was a “Cavaliere” in the Order of the Crown of Italy, the equivalent to “Sir” in Great Britain. He remained loyal to the King and became second in command of “MARIASSALTO”. The unit was based in the southern Italian city of Taranto, alongside the British frogman force in the Mediterranean.

Guys like Luigi Durand de la Penne and Antonio Marceglia, who had been taken prisoner by the British during an attack on the British Naval Base in Alexandria, were released from prison and joined “MARIASSALTO”.

In June 1944, members of “MARIASSALTO” carried out an attack against the occupied port of La Spezia. To prevent the Germans from using Italian cruisers as blockships to obstruct the harbour entrance, “MARIASSALTO” sank the “Bolzano” and damaged the “Gorizia” with a chariot (essentially the British copy of the Maiale). A plan to attack German U-Boats with Gamma frogman failed.

In Autumn 1944, Antonio Marceglia from “MARIASSALTO” travelled undercover to Valdagno and met with Borghese. It was only a matter of time until the Allies would liberate Italy and the biggest concern was that the Germans could destroy the Italian industries and ports of the north on their retreat. Borghese was urged to protect Italian interests.

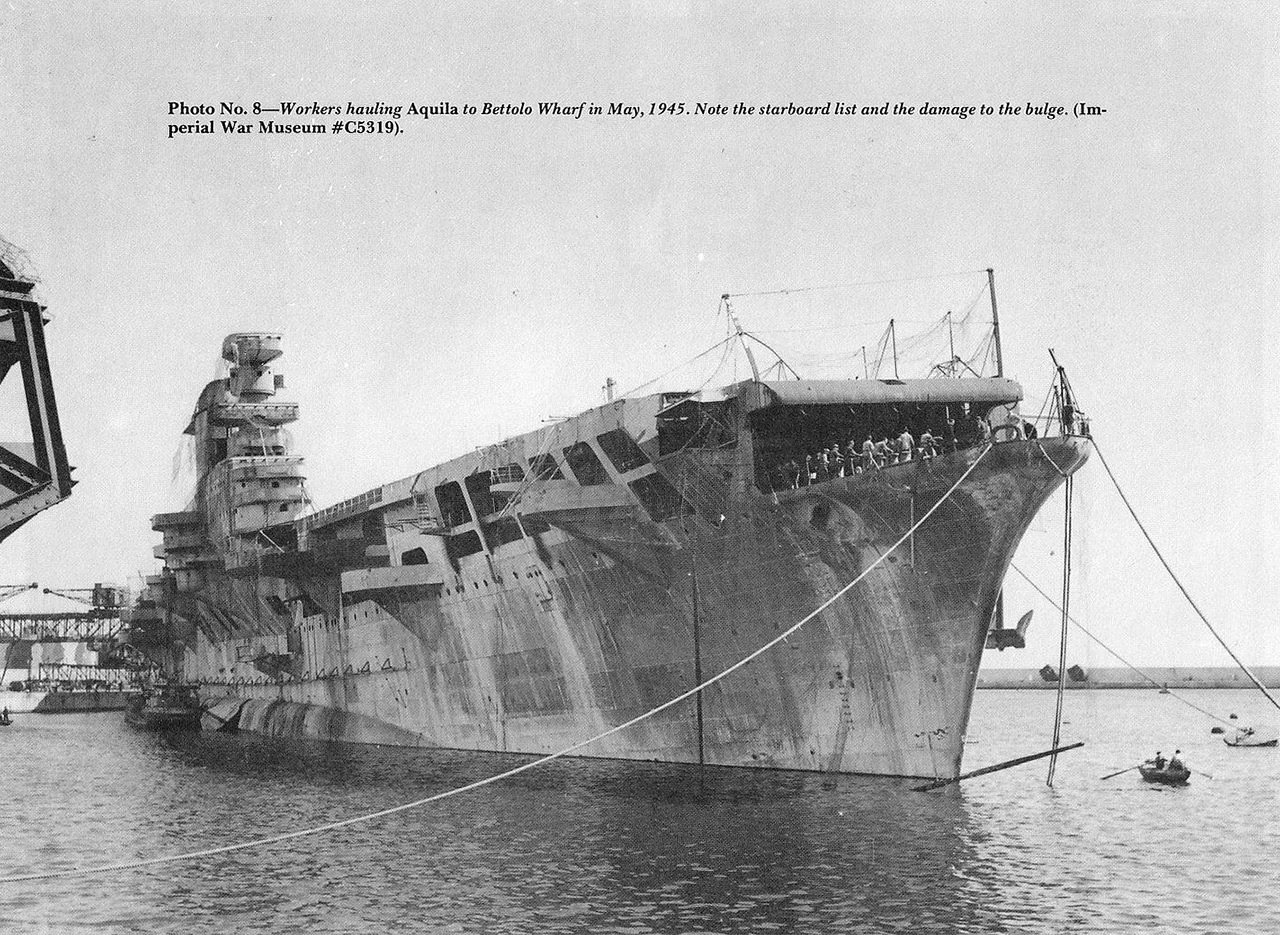

On April 19, 1945, “MARIASSALTO” striked again. This time in the port of Genoa, where the abandoned and stripped down Italian aircraft carrier “Aquila” was attacked with two chariots before it could be used to obstruct the harbour entrace. There is some controversy as to how successful this attack was. According to latest research, the “Aquila” did not sink nor was an explosion ever reported.

As a matter of fact, the Germans used the “Aquila” to block the narrow passage between the outer harbor and the larger basin but failed to sink her. The picture below shows the “Aquila” afloat in May 1945.

The war in Italy ended in late April 1945. Borghese’s Decima Flottiglia MAS was disbanded. According to British plans, Borghese was to be interrogated and passed on to the partisans for immediate execution. The Americans, however, rescued him and his wife as he was of crucial importance for his knowledge in fighting communism. Another reason for his survival can probably be found in the very fact that he belonged to an influential family of the Roman aristocracy. Borghese was brought to Rome where he was sentenced to 12 years in prison for collaborating with the Nazis and fighting the partisans. He was released after four years.

Lieutenant Eugenio Wolk, leader of the “Gruppo Gamma” under Borghese, divided his unit into small cells and sent them to Genoa and La Spezia, to prevent the Germans from destroying these ports. Wolk, together with a handfull of his most trusted men, went to Venice where Allied forces had already taken over the city. His initial plan was to protect the port from German sabotage acts and attack Allied ships once they arrived. Captain Ernesto Forza of “MARIASSALTA” convinced him to let go of this idea.

For the Allied secret services, Wolk was a character of major importance. He had been on their radar since 1943/44.

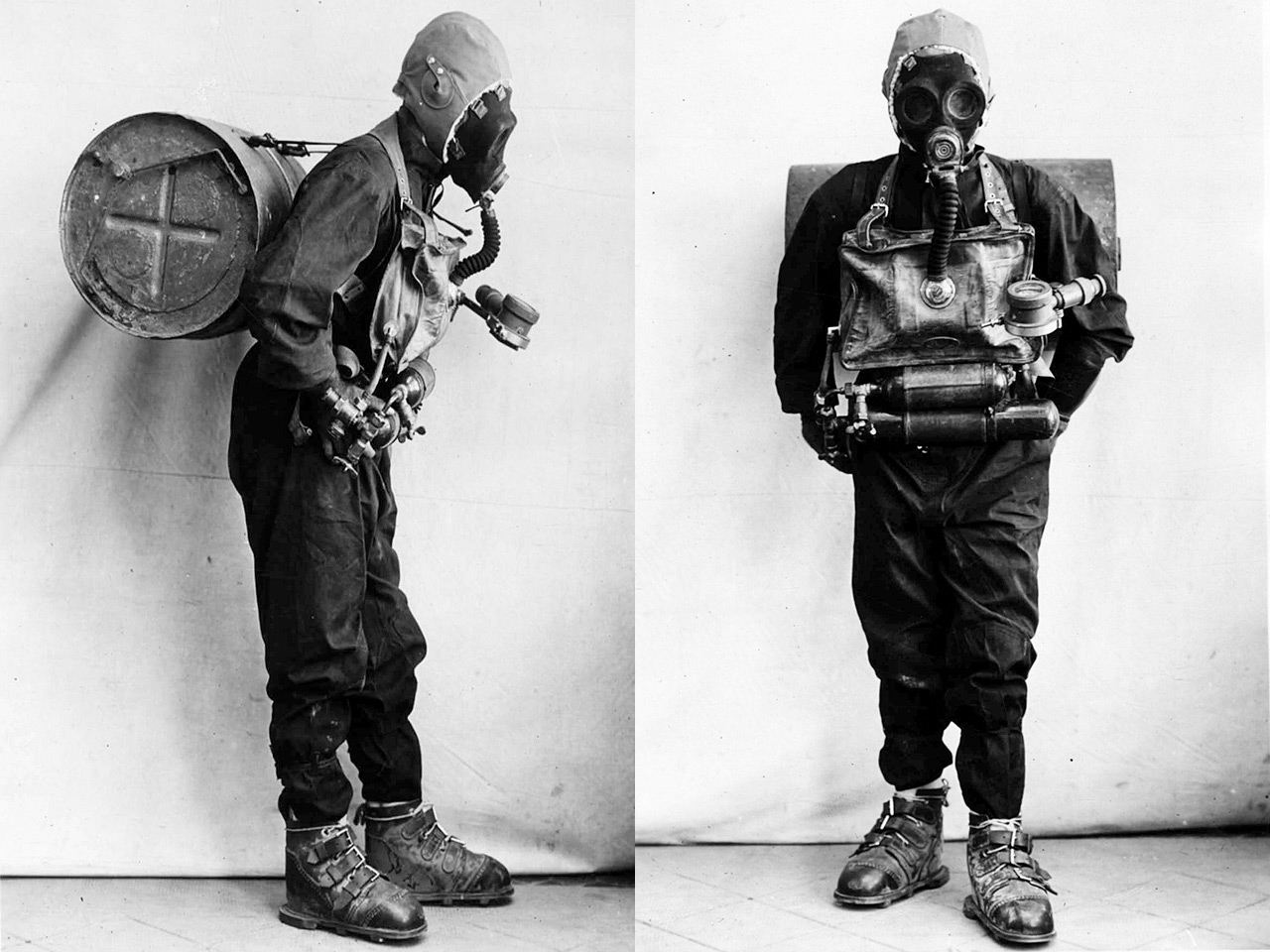

In January 1941, Wolk was sent to the diver school in Livorno to assist Commander Angelo Belloni in developing an underwater infantry. Belloni’s idea was simple. A diver, equipped with a 50 kg explosive charge on his back, would be released from a submarine and march on the seabed up to 10 km towards enemy harbours, attach the charge to a target and then march back to the submarine.

Wolk quickly understood Belloni’s idea was impossible to realize. The divers were subjected to all disadvantages of water and forced to march on loose, muddy seafloors. After just a few hundred meters, the divers had to surface as they were completely exhausted. To overcome these obstacles, Wolk envisioned a solution where the divers could take full advantage of the water.

In late 1941, Wolk developed the very concept of what nowadays is commonly referred to as “frogman”; an assault warrior who invisibly swam long distances towards enemy ships to attack them with small charges. To make this possible, Wolk developed a slim fit rubber suit and the very first Italian swimfins. The latter gave the swimmer the appearance of a “uomo rana” (= frogman), which coined the name ever since. Wolk also modified existing rebreathers to make them more efficient for his purpose.

Wolk and his men surrendered to the British in Venice and were granted the special title of “prisoners of war at large”. Wolk met Lieutenant Commander Lionel “Buster” Crabb, the famous Decima MAS hunter of Gibraltar, and was immidiately hired to take part in the newly established “Allied Navies Experimental Station” on the island of Sant Andrea, where he helped clearing the harbour from mines, shipwrecks, etc.

.

Post war period

The war was disastrous for Italy, especially after the Armistice with the Allies and the following occupation by the Germans. The victorious Allied powers forced Italy to give up some of its territory and pay war reparations to several countries. The Paris Peace Treaty also imposed heavy restrictions on the Italian armed forces. The development of assault crafts like the Maiales or explosive boats were prohibited.

To earn a living, ex Decima MAS divers used their skills to clear Italian ports from shipwrecks, mines and unexploded ordnance. In La Spezia alone, the retreating German troops had scuttled more than 320 ships of all sizes to block the harbour. Thousands of mines were scattered all around, ready to explode.

Under the cover of these operations, “MARIASSALTO” remained active and reorganized under the new name “MARICENTROSUB”, still with Ernesto Forza at the helm. Lieutenant Commander Amedeo Vesco (Capitano di Corvetta) was the second in command.

In mid 1946, the Italian people voted to abolish the monarchy and Italy became a republic. The Italian Navy formerly known as Regia Marina was renamed in Marina Militare.

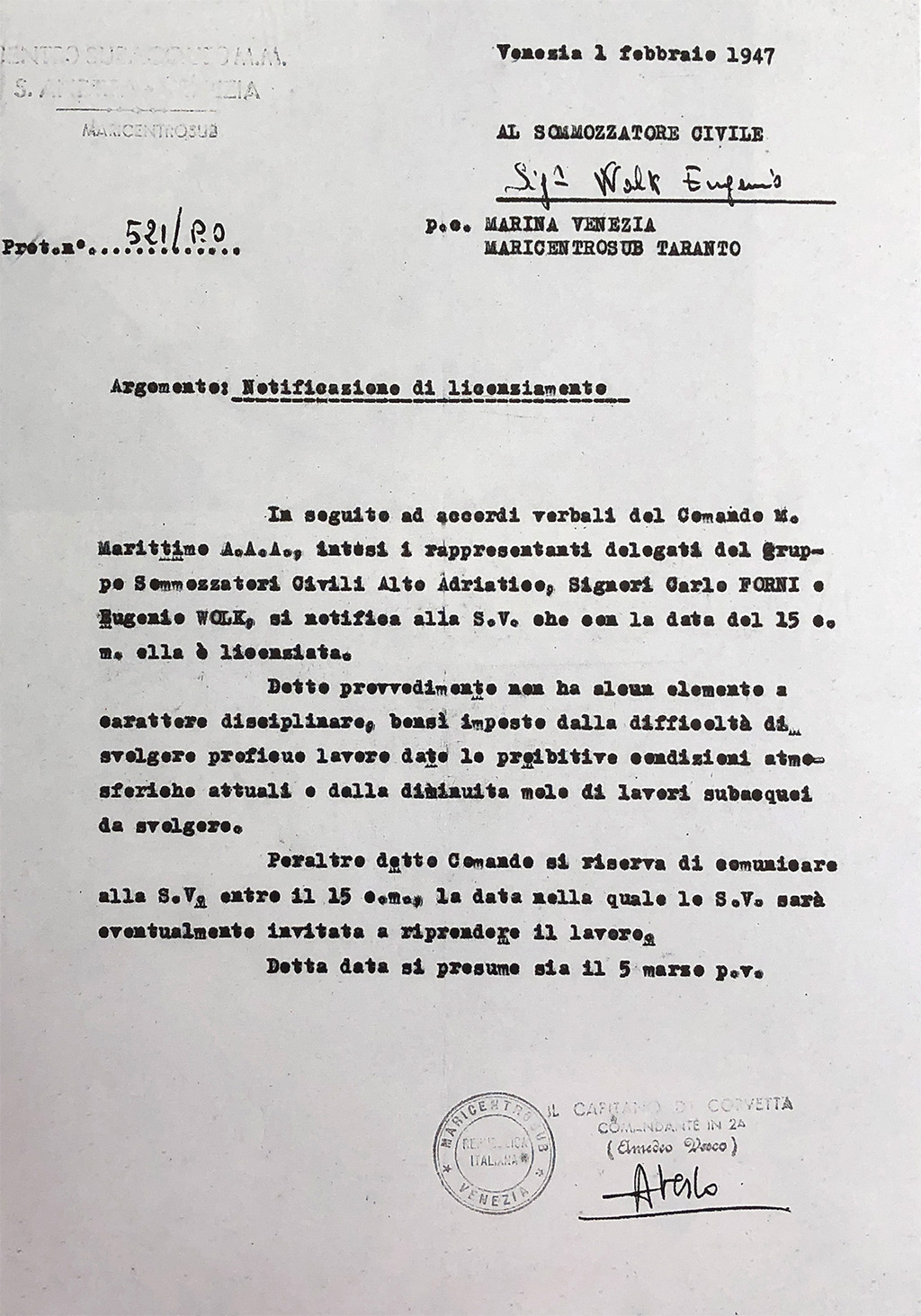

The next document is the reason why Eugenio Wolk’s story was of importance earlier on. In February 1947, Lieutenant Commander Amedeo Vesco signed Wolk’s letter of dismissal. Interestingly, Wolk was referred to as “civilian diver”. The reasons for Wolk’s dismissal are stated as bad weather conditions (winter) and a decreased demand for underwater labour. But there was more to it.

Men like Wolk, who served in units which collaborated with the Nazis after Sept. 1943, were not permitted to re-join the Italian Navy. To make matters worse, ex partisans were sometimes hunting them down. Wolk was safe as long as he was a British “prisoner of war” but when the “Allied Navies Experimental Station” was abandoned in 1946, Wolk faced a difficult situation. Together with his family, he decided to start a new life in Argentina. When the Argentinian authorities realized who he was, they immediately hired him to establish the first Argentinian underwater unit.

In April 1949, Italy became a member of NATO but it was not until end of 1951 that all the Paris Peace Treaty restrictions were revoked. As a result, the Italians started to officially rebuild their assault units on a larger scale. The units moved into the Varignano Fortress in Portovenere, where many of the remaining assault crafts and equipment had been secretly shipped.

The divers were still using their watches from WW2 but after so many years, the zinc sulfide in the radium lume was burned out and the dials were no longer visible in darkness. Many of these early watches were later upgraded with new dials and hands by Panerai in order to remain in service.

It was probably during this period that Panerai created a prototype middle case with solid lugs to improve Ref. 3646. The wire lugs of said reference, especially of the first batches, were prone to tear off under certain circumstances. To overcome this problem and keep Ref. 3646 in service, Panerai created a new middle case with lugs carved out of the same block of steel as the case.

The next picture shows the watch in question. This picture was found in G. Panerai e Figlio’s photo archive from the 1950/60s.

One of these prototypes was in use with the assault units of the Marina Militare as you can see in the following picture from the 1950s.

.

The new middle case with solid lugs was without doubt an improvement in terms of rigidness but did nothing to solve another problem. These 4-piece cases were not easy to service and maintain, since the construction remained basically the same.

The illustration below shows a Rolex Oyster case from 1926. Ref. 3646 had the very same construction.

The central part of this case, the core so to say, consisted of movement, dial and a movement retaining ring with external threads. This ensamble sat loose in the middle case. Bezel and case back were screwed onto the external threads of the movement retaining ring, rotating in opposite directions and literally clamping the middle case between them to form, with the help of two lead gaskets, a hermetically sealed body. Sounds complicated? It was!

People who have worked on such a case know how tricky it can be to put back together properly. Especially to correct stem alignment can cause sleepless nights, not to mention the watertightness issue.

The Marina Militare wanted probably to maintain their watches inhouse and these cases caused lots of headache. By the 1950s, Rolex had developed a new generation of Oyster cases that were much easier to maintain.

At some point, Amedeo Vesco was promoted to Commander (Capitano di fragata). From May 1, 1950 to Sept. 30, 1950, Vesco served as Commander of the semi clandestine unit named “MARICENTROSUB”. He was succeeded by Ernesto Notari, but only a few months later, from Mar. 15, 1951 to Apr. 30, 1954, Vesco became again Commander of the now renamed unit “MARICENT.ARD.IN.”

Reference: http://www.anaim.it

Coming back to the video I mentioned earlier, the man in camouflage uniform between the two guys in white could be Commander Amedeo Vesco.

Note that he and the other guy in camouflage, both are wearing huge Panerai watches. The guy on the far left is probably Aldo Massarini, another known commander of these units. If this is indeed Amedeo Vesco, it is very much possible that he was wearing his 6152.

In 1953, Rolex created a new state of the art watch for Panerai, the elusive Ref. 6152. Not many examples were produced which could be an indication that Ref. 6152 was originally conceived as a test model. At first glance, Ref. 6152 looked very similar to Ref. 3646 due to its iconic cushion-shaped case. The most notable improvement with respect to Ref. 3646 were the solid lugs, which were carved out of the same block of steel as the case.

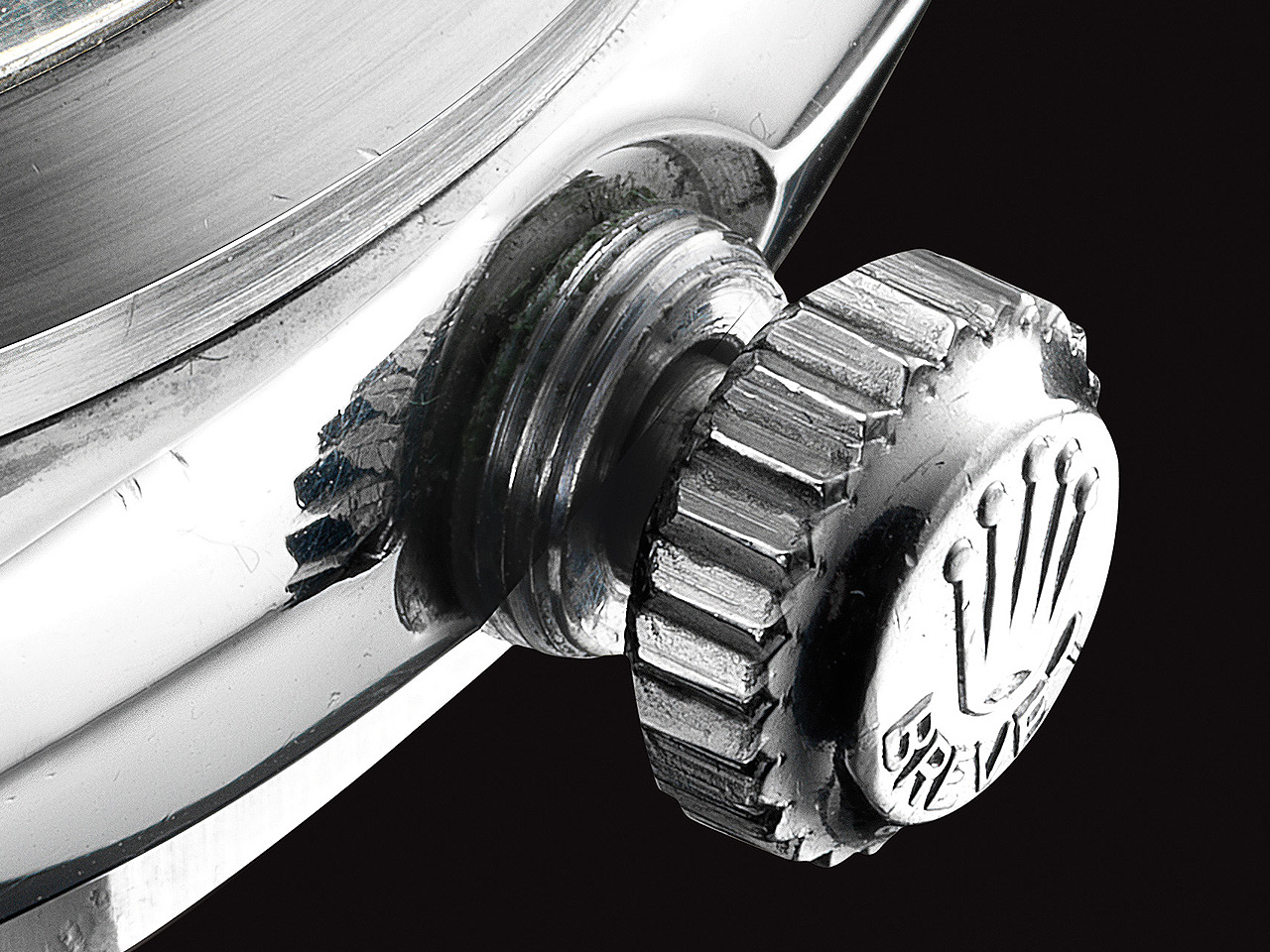

On Ref. 3646, the crown was protruding and prone to be easily damaged. An important detail of the 6152 case is the recessed area underneath the crown. This was probably Rolex’s first attempt at providing some sort of protection for the crown.

When fully screwed down, the crown of Ref. 6152 sits deep in its recession. The picture on the right has superimposed crown guards of the current Rolex Submariner to give you an idea.

Most improvements were invisible to the eye though, as they happened on the inside of the case. The plastic crystal was now pressure fitted onto the case itself. The outer bezel was also pressure fitted but had no other function than to cover the crystal seating.

The inside of the case had steps to provide a proper seating for the movement retaining ring, which put an end to stem alignment issues.

The picture below shows Vesco’s 6152 in profile. The side of the large case is adorned with an elegant crease. This is Art Deco design at its best!

As mentioned earlier, Ref. 6152 – and Ref. 6154 for that matter – could be considered testing prototypes in the process of creating the ultimate diver watch for the assault units of the Italian Navy. Both references were produced in very small numbers. The known case number range of Ref. 6152 expands from 956629 to 956643, and from 958697 to 958713. That is equivalent of around 30 pieces.

Ref. 6154 has a known case number range from 997572 to 997607, which suggests a total amount of 35 watches.

It appears that Ref. 6152 prevailed in the tests cause in 1955, Rolex created a new reference for Panerai named Ref. 6152/1. Around 500 pieces were made. This new reference was a “reduced to the max” version of Ref. 6152. The crease around the case was dropped, as was the recession for the crown. The clamps movement retaining ring were dropped as well. Overall, the whole watch was simplified, probably to save costs and make it easier to maintain.

The movement used in Ref. 6152 was the very same Cortebert Cal. 618 as in Ref. 3646, just slightly less refined with only 15 jewels instead of 17 jewels. The overcoiled Breguet hairspring was retained.

Vesco’s watch in the picture below is perfect in this regard.

The movement retaining ring is held in place by three casing clamps. Interestingly, in Ref. 6154 and 6152/1, these clamps were dropped.

The movement retaining ring was an essential part of the early Oyster case construction. This part was not necessary in Ref. 6152 as the case could have easily been machined to the precise movement diameter. The fact that such a ring was installed says a lot about the concept of these watches. Obviously, Panerai wanted to be flexible and was perhaps already playing with the idea of installing Angelus 240 8-Day movements.

Cortebert-made movements were anti magnetic but to further shield the movement against magnetic fields emitted by limpet mines, etc. the caliber of Ref. 6152 was “caged” with a magnetically permeable soft iron cover.

The case back of Ref. 6152 bears the typical Rolex hallmarks used during this period of time. Rolex case number 956638 is from 1953. In 1954, Rolex started from 0 again, that’s why Ref. 6152/1 from 1955/56 has case numbers in the 124500 range.

The outside of the case back of Ref. 6152 bears the inscription “Registered Design – Modèle Déposé”.

The very same inscription can also be found on other Rolex Oyster watches from 1953.

.

Thoughts

Amedeo Vesco’s 6152 is without a doubt an extraordinary piece. It was first sold by Vesco’s son in 2008 and can be considered an important piece of Italian history. At the same time it is also a historically important diver watch for both, Rolex and Panerai. Items of this category should actually be exhibited in a museum. The watch appears to be in untouched original condition. The only downside is the missing original strap.

In Oct. 2017, I had the chance to help an important vintage Panerai collector restore his precious 6152 with case numner 956636 to original condition. The watch had passed through the hands of the usual suspects and the original dial was replaced with a fake Rinaldi dial. I was able to source the original dial and interestingly, the numeral at 6 o’cock has the very same brittle effect as Vesco’s watch.

Read more: Vintage Panerai – The mysterious bluish tinted dials

Thank you for your interest.

.

The Panerai Time Machine

Ref. 6152 is an important piece of the Panerai puzzle. The infographic below shows all vintage Panerai watches in their historical context. Please click the graphic to download the highres version.

This timeline is available as a high quality print in two sizes:

- 120 x 68 cm (47 x 26 inch): EUR 85.00 (plus shipping)

- 150 x 85 cm (59 x 33 inch): EUR 120.00 (plus shipping)

Printed with HD Inkjet on heavy synthetic paper and laminated.

Limited edition: 50 pieces, numbered and signed by Maria Teresa Panerai in Giuseppe Panerai’s very own laboratory at the historical site of the Villino Panerai (Panerai Villa) in Florence: Sold out

More information: The history of Panerai watches at a glance