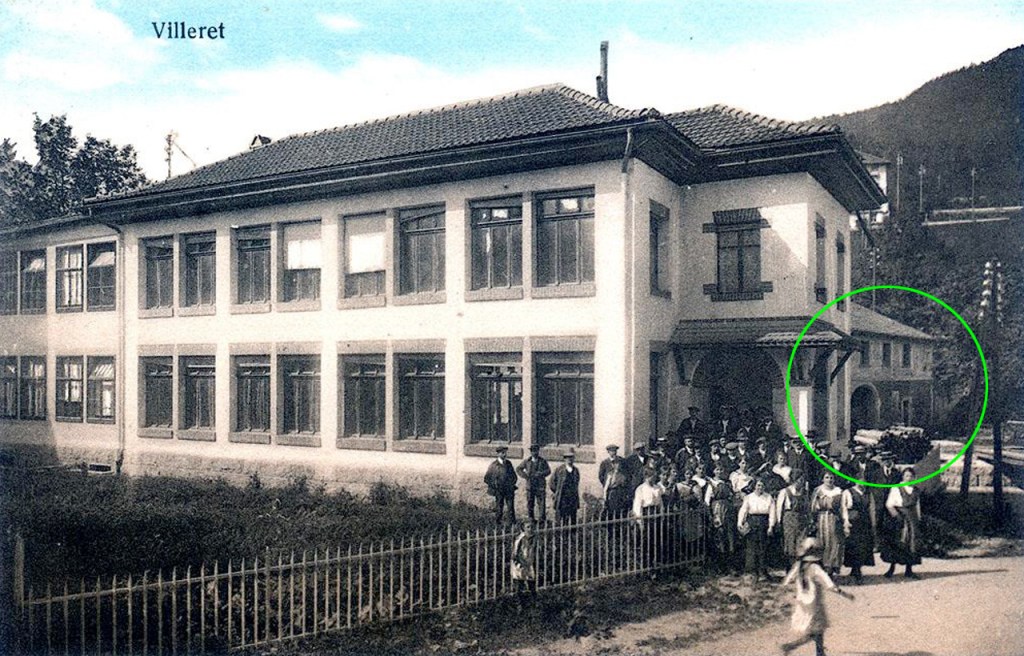

The modern Blancpain brand boasts about having been founded in 1735, thus being the oldest watch brand in the world. Older than Vacheron Constantin and Breguet, both of which have the receipts to prove their age, but on how much fact, if fact at all, is Blancpain’s founding date based? The modern Blancpain brand seems to have a weird obsession with superlatives. Oldest watch brand in the world, first modern dive watch. You get the idea. Made into a moon phases-wielding luxury brand in the 1980s, original Blancpain products were anything but luxurious. According to the modern Blancpain brand, 1735 is the year a certain Jehan-Jacques Blancpain registered himself as a watchmaker in the village rolls of Villeret, a tiny village in the Swiss Jura. The original record, however, was never produced. Instead, Blancpain shows a weird fake ancient script on their website. In old ads from 1900, however, the founding date was 1815. I recall perfectly when Blancpain launched the one million Swiss Francs ‘1735 Grand Complication’ in the 1990s. Little did I know back then that one day the history of this brand would make me dig into 18th century records for months in a row. Speaking of records, a big thank you to Swiss historian Rossella Baldi for her precious help.

This article is a long read. For those not wanting to go through the minutiae, namely all the tiny details, family trees, archive extracts, advertisements, and references, please keep reading. For the full story, click here.

Long Story Short

The original Blancpain company never claimed the founding date of 1735. In all communication up to 1953, the founding date was always stated as 1815. In none of the contemporary publications up to 1959 was the purported founding father Jehan-Jacques Blancpain ever mentioned. Historians like Emile Bourquin and Dr. Marius Fallet, who researched the history of the introduction of watchmaking in the Jura to exhaustion and published articles about it more than 100 years ago, never mentioned Jehan-Jacques Blancpain, his son Isaac, or his grandson David-Louis as having been watchmakers. If we go through the parish records (church records) of the 18th century, neither Jehan-Jacques nor his son Isaac or his grandson David-Louis were ever listed as watchmakers.

According to the available data from before the 1950s, the founding father of the Blancpain company was Frédéric-Louis Blancpain (1786 – 1843). Frédéric-Emile, the last of the Blancpains to lead the company died in 1932 (1863 – 1932). In 1933, the business was acquired by two employees, Betty Fiechter and André Léal, and subsequently renamed Rayville. At the time, the law did not allow the Blancpain name to be kept since no family members were involved in the business. In 1950, Betty Fiechter’s 23-year-old nephew, Jean-Jacques, still a student, started working at Rayville. Almost immediately, he began playing around with the history of Blancpain, hinting at an earlier founding date than 1815. It seems he was only just learning about the history of watchmaking as he confused important details and tried to make believe, the Blancpains had been in the watch business since 1636, which actually was the construction date of the oldest house in Villeret, located right next to the Blancpain factory. Later it was claimed the 1636 house was the cradle of the Blancpain watchmaking clan, farming on the ground level and watchmaking upstairs. However, I could not find evidence to support the story. It was not until 1959 that Jehan-Jacques Blancpain was first mentioned. A narrative similar to what is perpetuated today by the modern Blancpain brand, was first recounted in a Rayville advertisement in 1968. However, the ad made the vital mistake to claim Jehan-Jacques Blancpain was making watch with his son Isaac in 1735, but at the time, Isaac was only a few months old as he was born in 1735. Whoever created that story did not research the family well.

The modern Blancpain brand was created from scratch in 1983. There was nothing except the name ‘Blancpain’, because the brand had ceased to exist in around 1975 when the Rayville company was slowly but surely swallowed by Omega. In 1983, Jaques Piguet and Jean-Claude Biver bought the name rights for ‘Blancpain’ for CHF 20,000 from Omega and set up a new company in Le Brassus, far away from Villeret, the birthplace of Blancpain. In 1992, Blancpain was sold to what is now the Swatch Group.

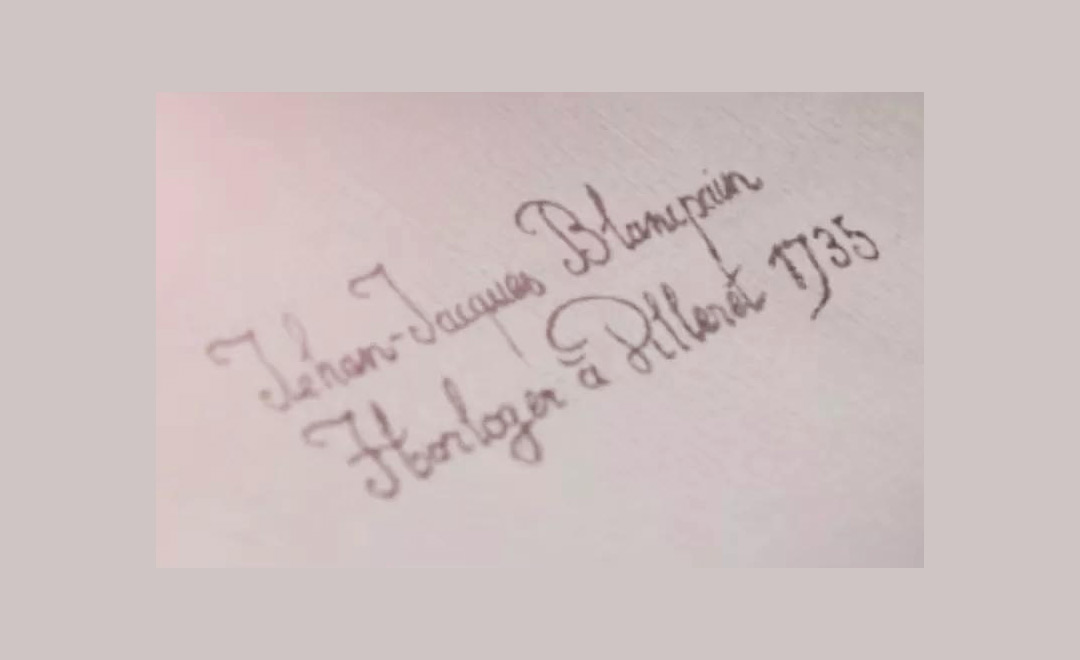

The modern Blancpain’s claim to be the oldest watch brand in the world is based on a mysterious record from 1735 in which Jehan-Jacques Blancpain purportedly registered himself as a watchmaker. Interestingly, the original record has never been produced, which is strange as watch companies love to show off old documents. In the history section of their website, Blancpain presents a fake record which was created as part of a video in 2015.

Some time ago, I contacted the village council of Villeret and asked for the record, but was told they searched on numerous occasions on behalf of Blancpain without success. They do not have the record in question. After I called Blancpain out on their fabricated history in September 2023, a professional archivist is now searching the Archives of the Bishopric of Basel on behalf of the brand. Said archives were mentioned by Blancpain in one of their publications back in 2008. It appears they never saw nor had the record to begin with and are now scrambling to find it. Basically, they have been claiming the title of the oldest watch brand in the world without evidence, based solely on Jean-Jacques Fiechter’s alteration of the Blancpain history in the mid 1950s.

I also reached out to Blancpain and their in-house historian Jeffrey Kingston to ask for the original 1735 record but was ignored. Yesterday after four long weeks of radio silence, Blancpain’s Head of Marketing Alexios Kitsopoulos sent me an email. Not to provide the 1735 record as previously requested, but to soft-soap me via a proposed tasty lucheon date to “better understand my motivation”. It seems people just cannot grasp when others are not motivated by money but solely by the pursuit of truth.

Please continue reading for the full story or click here for my final thoughts on the matter.

The Full Story

Important Developments

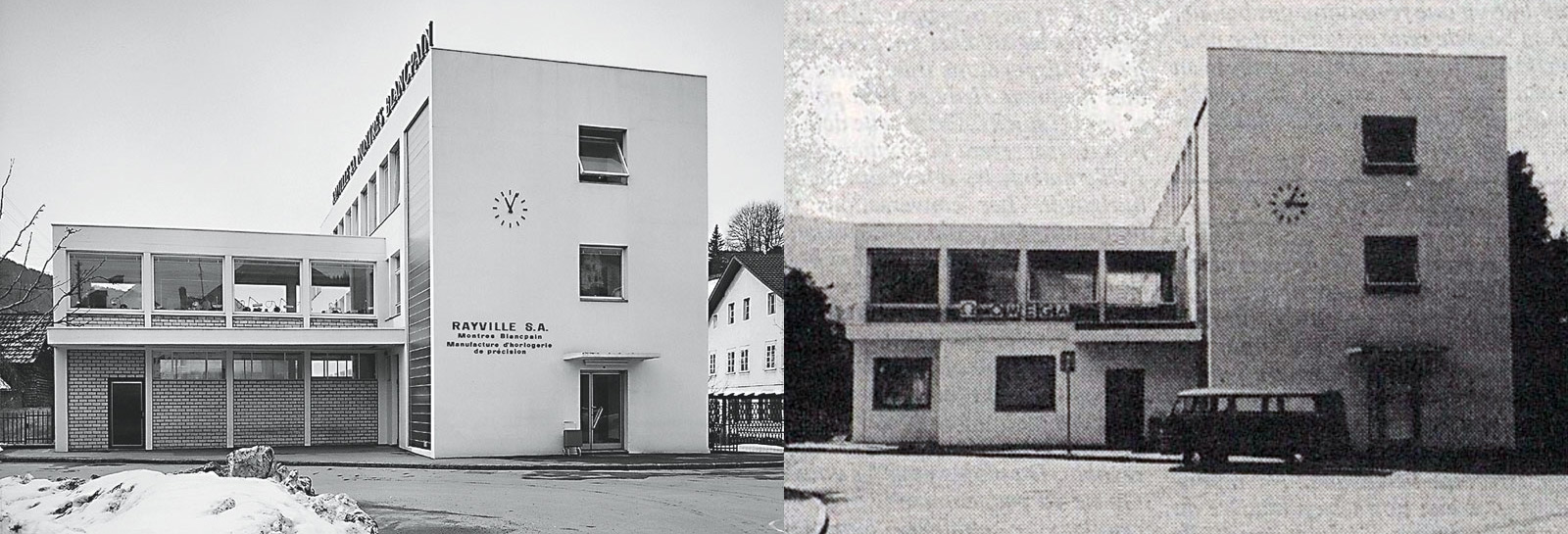

The history of modern Blancpain as perpetuated today was shaped by three crucial events. The first was the sudden death of Frédéric-Emile Blancpain on September 4, 1932, the last of the Blancpain family to lead the company. Having no one in the Blancpain family wanting to continue the watch business, the company was acquired by two employees, Betty Fiechter (1896 – 1971) and André Léal. At the time, the law did not allow the Blancpain name to be kept as no family members were involved in the company. Consequently, the business was renamed Rayville S.A., a phonetic anagram of Villeret, the small village where the company was founded.

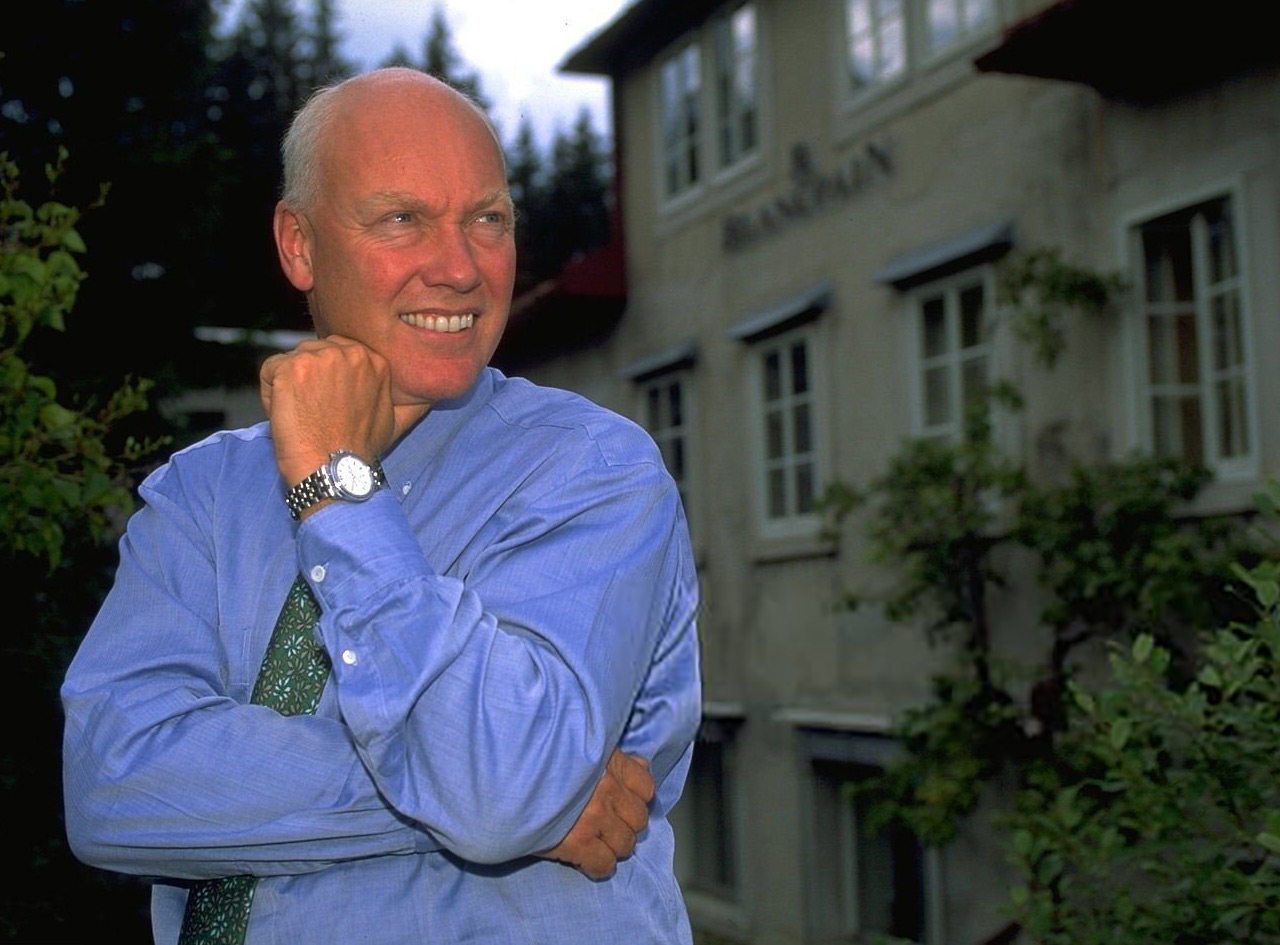

The second and more important development, starting in 1950, was Jean-Jacques Fiechter (1927 -2022), Betty Fiechter’s young and dynamic nephew, taking over the Rayville leadership. It was him who started playing around with the founding date of Blancpain. While Betty Fiechter left the history of the brand untouched throughout her reign, her nephew, a mini Hans Wilsdorf on steroids, had a different vision for the company.

The third and last occurrence important mentioning is the resurrection of the dead Blancpain brand in 1983 by Jacques Piguet and Jean-Claude Biver. Bought for CHF 20,000 from Omega, there was nothing except the name. No factory, no tools, no stock, no employees, no archives, niet, nada, nothing. What had happened to Rayville/Blancpain? After becoming part of SSIH or Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère (Swiss Society for the Watch Industry) in 1961, Rayville started producing movements for Omega. Eventually, SSIH was restructured and all watch companies belonging to the group were put under the control of Omega. The Blancpain brand vanished around 1975. Rayville became a full-time movement manufacturer for Omega in addition to producing quartz pocket watches under the Moeris brand. In 1980, the Rayville company was dissolved and all assets, including the factory, were swallowed by Omega and turned into their jewelry department.

The name rights for ‘Blancpain’ were transferred to Omega. In 1982, now in big trouble due to the quartz crisis, Omega withdrew from Villeret, abandoning the former Rayville factory completely and causing a major uproar in the village. In 1983, the modern Blancpain brand was created from scratch, far away from Villeret, the birthplace of Blancpain in the Bernese Jura, at the site of Frédéric Piguet S.A. in Le Brassus located in the famous Vallée de Joux. Modern Blancpain is an artificial construct with zero ties to the original company, the Blancpain family and their horological legacy.

The Blancpains

To understand the history of Blancpain as perpetuated by the Swatch Group it is important to know the characters involved and have an idea of the Blancpain family tree. Blancpain’s purported founding year of 1735 revolves around the mysterious figure of Jehan-Jacques Blancpain, said to have been the first of a nearly 200 years long and uninterrupted succession involving seven generations of Blancpain watchmakers.

Isaac (Maître Cordonnier, master shoemaker)

1670 – 1724

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

1. Jehan-Jacques

1694 – ~1770

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

2. Isaac (Regent d’école, head of school)

1735 – ~1803

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

3. David-Louis

1765 – 1843

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

4. Frédéric-Louis (Le Jeune)

1786 – 1843

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

5. Frédéric-Emile (E. Blancpain)

1811 – 1857

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

6. Jules-Emile (E. Blancpain & fils)

1832 – 1928

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

7. Frédéric-Emile (E. Blancpain fils/Blancpain)

1863 – 1932

According to the modern brand, Jehan-Jacques Blancpain was baptized on March 11, 1693.

“It was in Villeret that Jehan-Jacques Blancpain was born; his baptismal certificate is dated March 11, 1693.”

Source: Lettres du Brassus, Issue 04, 2008 (PDF, blancpain.com)

Here we already have the first problem. Jehan-Jacques Blancpain was baptized one year later on March 11, 1694. A basic archival search would have made this clear.

Source: Excerpt baptism register St-Imier from 1694 (State archive Canton of Bern)

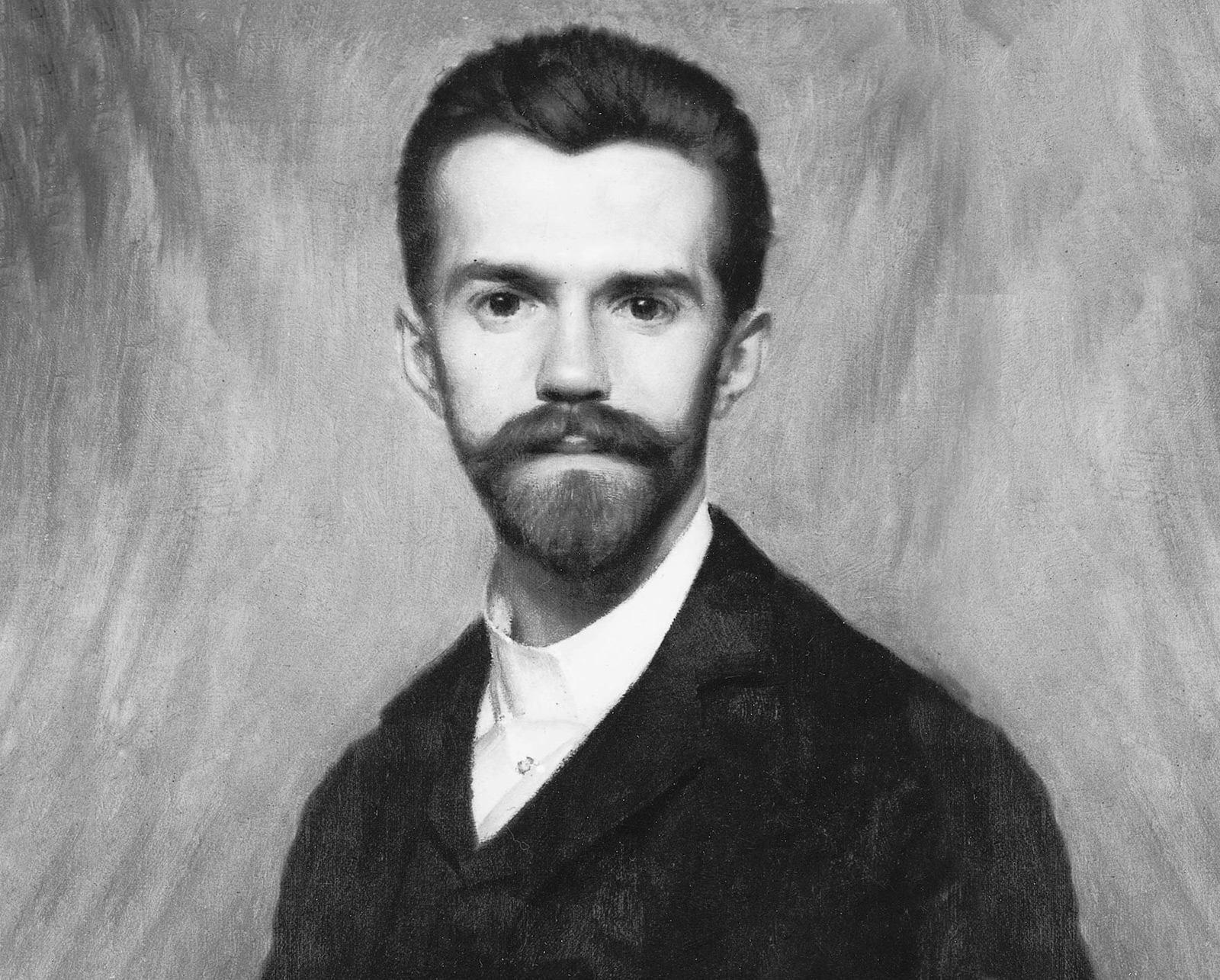

The portrait below shows what Jehan-Jacques Blancpain supposedly looked like, at least that was Blancpain’s storyline during the Jean-Claude Biver years (1983 – 1992) and up until around 2007 under the Swatch Group. Then, the portrait suddenly disappeared from all communication.

In 2008, it was revealed the portrait (without showing it) was not a depiction of Jehan-Jacques Blancpain but of Frédéric-Emile Blancpain (1863 – 1932).

“However, in celebrating its pedigree and paying homage to Jehan-Jacques, a portrait of a distinguishedlooking bearded gentlemen has been held out as his. Indeed that portrait is of a Blancpain family member, just not Jehan-Jacques; it is of Frédéric-Emile Blancpain who lived fully a century and half later.”

Source: Lettres du Brassus, Issue 05, 2008 (PDF, blancpain.com)

Rumour has it Jean-Claude Biver found a random portrait somewhere in a flea market and bought it with the idea of putting some flesh on the bare bones of the freshly resurrected Blancpain brand. Biver is said to have bragged about this episode among friends. Once the Swatch Group got wind that the story had gone public, they immediately retired the portrait. Having seen Biver boast about similar stories on camera, it is easy to believe the rumour to be true.

Fact is, the painting vanished from official Blancpain material, never to be seen again, but that did not stop some of the mainstream watch media outlets from unearthing and continuing to use it in their unreflected copy-and-paste articles on the history of Blancpain.

According to the modern Blancpain brand, Jehan-Jacques was not only a watchmaker but also a farmer. Oh, and a teacher, and also the mayor of the village. Picture a hamfisted farmer making watches after a hard day at work. The story of the so-called ‘paysan horloger’ (farmer watchmaker) building watches during the long winter evenings is of course more of an old romantic myth the Swiss like to tell to this day. As historians like Dr. Marius Fallet (1876 – 1957) already wrote 100 years ago, the tale could not be further from the truth. Watchmaking in the Jura region and especially in Villeret did not result from farmers turning watchmakers but from gunsmiths, locksmiths, tool and nail makers, skilled artisans expercienced in metalworking branching into the new craft.

Watchmaking in the Jura valleys was introduced by watchmakers from Geneva in the late 17th century. At the time, the right to work as a master watchmaker in town was solely the privilege of citizens of Geneva. So-called ‘natives’, born in Geneva but descendants of foreigners, were excluded. This situation led to a veritable exodus of highly skilled craftsmen into more welcoming areas such as the Neuchâtel mountains and the Jura. It was only towards the middle of the 18th century that local Jurassien artisans started adopting watchmaking themselves. First in Tramelan, then Sonvilier and Villeret followed by Courtelary and St-Imier. The history of the introduction of watchmaking in the Jura was researched by respected historians like Emile Bourquin and Dr. Marius Fallet starting in 1886 and is well-documented. Interestingly, none mentioned Jehan-Jacques Blancpain or his descendents Isaac and David-Louis as being watchmakers. The Blancpains are only mentioned as jumping on the horlogical bandwagon in the early 19th century with Frédéric-Louis Blancpain ‘Le Jeune’ (1786 – 1843)* at the end of the 18th century with Frédéric Blancpain ‘Le Jeune’, at a time when the craft was long established in the region. The works of these historians were published in contemporary publications, giving the Blancpains ample opportunity to protest and set the record straight if crucial parts of their history were overlooked.

* Update, September 8, 2024

Attentive readers have pointed out that Dr. Marius Fallet mentioned Frédéric Blancpain ‘Le Jeune’ as establishing himself as ‘horloger-établisseur’ at the end of the 18th century, not in the early 19th century as written. I was aware of the discrepancy but assumed it was a slip. After careful consideration, it is more likely the lapse was on my part and Dr. Fallet was actually talking about the uncle of Frédéric-Louis Blancpain ‘Le Jeune’ (1786 – 1843), who was born in 1759 and apparently went by the very same nickname ‘Le Jeune” (the young). You see, the Blancpains were not very diverse with names. I had looked into the uncle’s records during my research but could not find any indication he was a watchmaker. Perhaps because a ‘horloger-établisseur’ was not a watchmaker in the literal sense but more of a watch merchant, an intermediary between market and production, who bought parts from various subcontractors and had them assembled in his workshop. Fallet mentioned that David-Louis Bourquin was Frédéric Blancpain’s main competitor at the time. Unlike Blancpain, Bourquin was listed as watchmaker (horloger) as early as 1779. In the grand scheme of things, this does not change much.

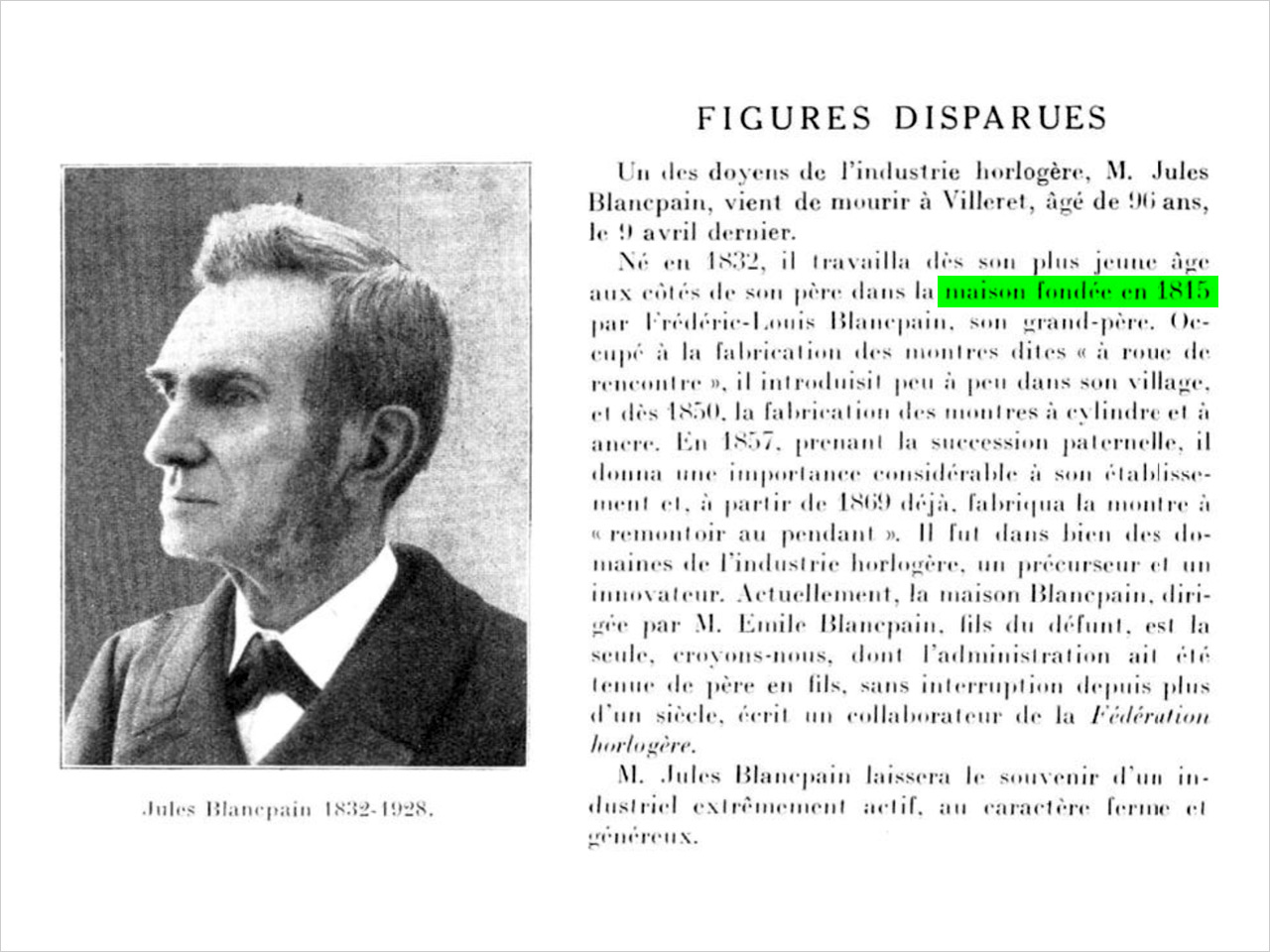

In addition, there is no indication that the original Blancpain company ever claimed their history goes back to 1735. The founding date was always stated as 1815, probably the year Frédéric-Louis Blancpain (1786 – 1843) established his own workshop. In the following obituary of Frédéric-Louis’ grandson, Jules-Emile Blancpain (1832 – 1928), published in the Swiss Horology Journal of May 1928, the founding date is stated very clearly.

“Figures Disparues

Un des doyens de l’industrie horlogère, M. Jules Blancpain, vient de mourir à Villeret, âge de 96 ans, le 9 avril dernier.

Né en 1832, il travailla dès son plus jeune âge aus côtés de son père dans la maison fondée en 1815 pas Fréderic-Louis Blancpain [1786 – 1843], son grand-père. Occupé à la fabrication des montres dites «à roue de rencontre», il introduisit peu à peu dans son village, et dès 1850, la fabrication des montres à cylindre et à ancre. En 1857, prenant la succession paternelle, il donna une importance considérable à son établissment et, à partir de 1869 déjà, fabriqua la montre à «remontoir au pendant». Il fut dans bien des domaines de l’industrie horlogère, un précurseur et un innovateur. Actuallement, la maison Blancpain, dirigée par M. Emile Blancpain [1863 – 1932], fils du defunt, est la seule, croyons-nous, dont l’administration ait été tenue de père en fils, sans interruption depuis plus d’un siècle, écrit un collaborateur de la Fédération horlogère.

M. Jules Blancpain laissera le souvenir d’un industriel extrêmement actif, au caractère ferme et généreux.”

Translation:

Deceased People

One of the deans of the watchmaking industry, Mr. Jules Blancpain, has just died in Villeret, aged 96, on April 9.

Born in 1832, he worked from a young age alongside his father in the company founded in 1815 by Fréderic-Louis Blancpain [1786 – 1843], his grandfather. Busy with the manufacture of so-called ‘return wheel’ watches, he gradually introduced into his village, and from 1850, the manufacture of cylinder and anchor watches. In 1857, taking over from his father, he gave considerable importance to his establishment and, already from 1869, manufactured the ‘pendant winder’ watch. In many areas of the watchmaking industry, he was a precursor and an innovator. Currently, the Blancpain house, managed by Mr. Emile Blancpain [1863 – 1932], son of the deceased, is the only one, we believe, whose administration has been held from father to son, without interruption for more than a century, writes a collaborator of the Watch Federation.

Mr. Jules Blancpain will be remembered as an extremely active industrialist, with a firm and generous character.”

Source: Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie, May 1928, Nr, 5 (watchlibrary.org)

Note the explicit mention that the family business was handed down from father to son, without interruption, for more than a century. The name Jehan-Jacques Blancpain is nowhere to be found. If Jehan-Jacques Blancpain (1694 – ~1770) was indeed the first watchmaker in the family, followed by his son Isaac (1735 – ~1805) and his grandson David-Louis (1765 – 1816), adding another 100 years of family tradition in watchmaking, would they not have stated so in this obituary published in a renowned Swiss publication about horology and read by the entire industry? Again, pretty sure the Blancpains would have protested and demanded a correction if this important part of their history was ignored. An errata, however, was never published.

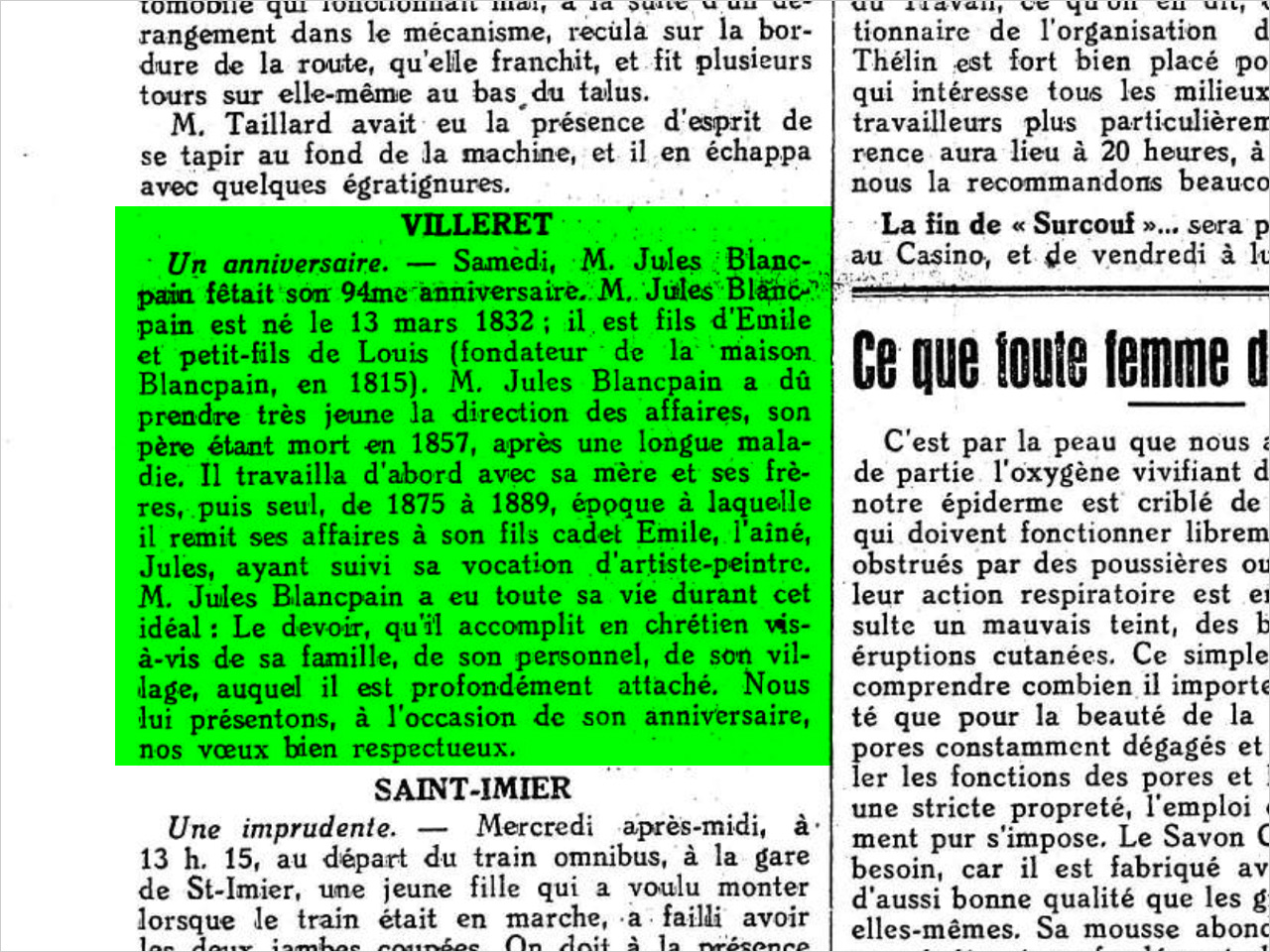

Earlier, when Jules-Emile Blancpain reached the impressive age of 94 in 1926, the newspaper La Sentinelle from La-Chaux-de-Fonds paid tribute with this announcement:

“M. Jules Blancpain fêtait son 94me anniversaire. M. Jules Blancpain est né le 13 mars 1832 ; il est fils d’Emile et petit-fils de Louis (fondateur de la maison Blancpain, en 1815). M. Jules Blancpain a dû prendre très jeune la direction des affaires, son père étant mort en 1857, après une longue maladie. Il travailla d’abord avec sa mère et ses frères, puis seul, de 1875 à 1889, époque à laquelle il remit ses affaires à son fils cadet Emile, l’aîné, Jules, ayant suivi sa vocation d’artiste-peintre. M. Jules Blancpain a eu toute sa vie durant cet idéal : Le devoir, qu’il accomplit en chrétien vis-à-vis de sa famille, de son personnel, de son village, auquel il est profondément attaché. Nous lui présentons, à l’occasion de son anniversaire, nos voeux bien respectueux.”

Translation: Mr. Jules Blancpain celebrated his 94th birthday. Mr. Jules Blancpain was born on March 13, 1832; he is the son of Emile and grandson of Louis (founder of the Blancpain house in 1815). Mr. Jules Blancpain had to take charge of the business at a very young age, his father having died in 1857, after a long illness. He worked first with his mother and his brothers, then alone, from 1875 to 1889, a time when he handed over his business to his youngest son Emile, the eldest, Jules, having followed his vocation as a painter. Mr. Jules Blancpain has had this ideal all his life: Duty, which he fulfills as a Christian towards his family, his staff, his village, to which he is deeply attached. We offer him, on the occasion of his birthday, our very respectful wishes.

Source: La Sentinelle, March 18, 1926 (e-newspaperarchives.ch)

Note the very specific information. No way this was public knowledge at the time. It can be assumed the newspaper reached out to the Blancpain family or business insiders for details. Once again, there was no word of Jehan-Jacques Blancpain, the elusive figure said to have founded the family business in 1735.

How 1815 Became 1735

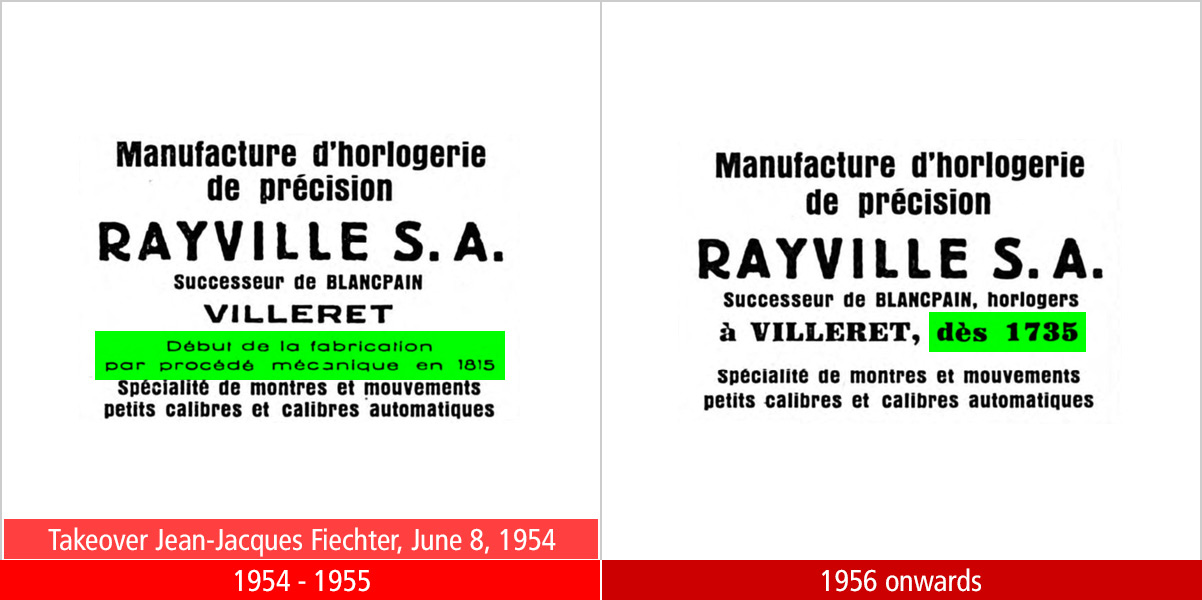

According to E. Blancpain fils advertisements from 1900 onwards, the maison (house) was founded in 1815. From 1918 onwards, it was specified by whom, Frédéric-Louis Blancpain (1786 – 1843), and who the current director was, Frédéric-Emile Blancpain (1863 – 1932). The latter took the company over in 1889, not 1915 as stated in the ad. This was probaly done to highlight the more than one century long existence (1815 – 1915). These ads remained practically the same until 1934, one year after the Blancpain family had given up the business following the sudden death of Frédéric-Emile Blancpain. For the next two decades until 1953, under the leadership of Betty Fiechter, the ads remained basically untouched with the only exception being the official name of the company which had become Rayville S.A.

Sources:

• Indicateur Davoine, 1900 (watchlibrary.com)

• Indicateur Davoine, 1935 (watchlibrary.com)

• Indicateur Davoine, 1953 (watchlibrary.com)

• Indicateur Davoine, 1954 (watchlibrary.com)

• Indicateur Davoine, 1956 (watchlibrary.com)

In 1954, Jean-Jacques Fiechter, the nephew of Betty Fiechter, became officially the director of Rayville S.A. and he immediately started altering the history of the brand. Instead of “Maison fondée en 1815” (House founded in 1815) as in the past, the new ads said: “Début de fabrication par procédé méchanique en 1815 “(Start of manufacturing by mechanical process in 1815). Note that the phrase is more or less what Blancpain stated in 1900, namely “Fabrique de montres par procédés mécaniques”. Hinting at an earlier, more artisan way of producing watch in the Blancpain family, Fiechter used this new ad for two years, setting the stage for the “oldest watch brand in the world” narrative. In 1956, finally, he came up with “Horlogers à Villeret, dès 1735” (Watchmakers in Villeret, since 1735).

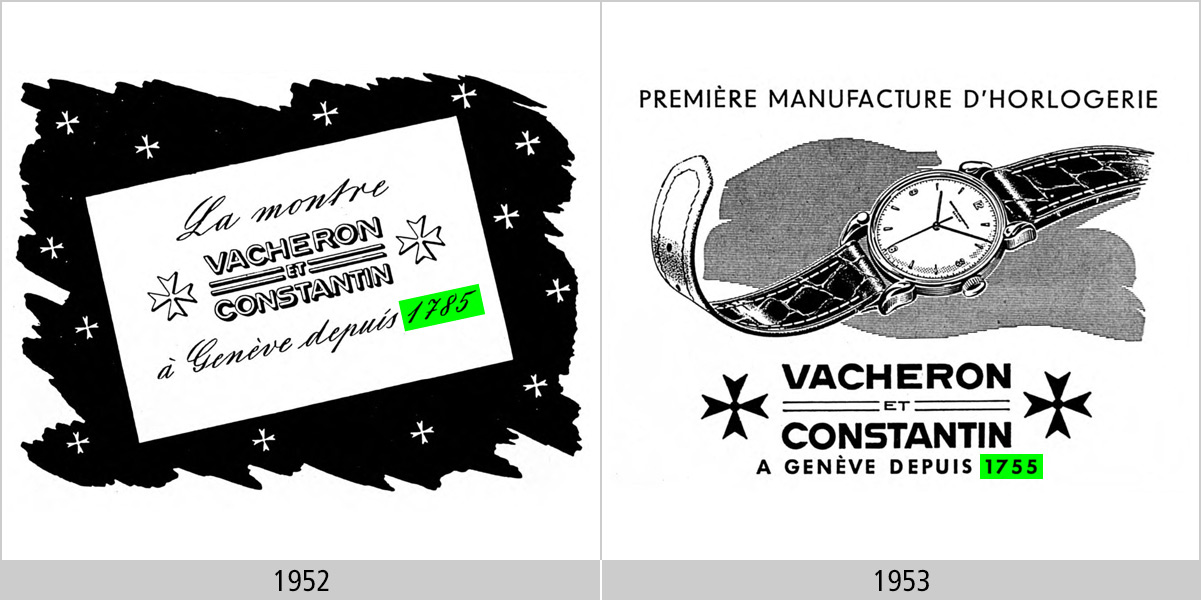

It is interesting to note that this was done after Vacheron Constantin updated their founding date from 1785 to 1755 due to the discovery of an apprenticeship contract, thus becoming the oldest watch brand in the world, 20 years older than Breguet (1775). It was also around the time historian Dr. Marius Fallet was very old and about to die. An explanation as to why this change occured was not given at the time, at least none can be found in the known archives. However, in June 1955 something noteworthy happened. American Blancpain importer Allen Tornek ran a Fifty Fathoms ad in the American Skin Diver magazine which claimed Blancpain were “Craftsmen since 1636”. Now, 1636 is actually the construction year of the oldest buidling in Villeret, claimed to be the cradle of the Blancpain watchmaking clan.

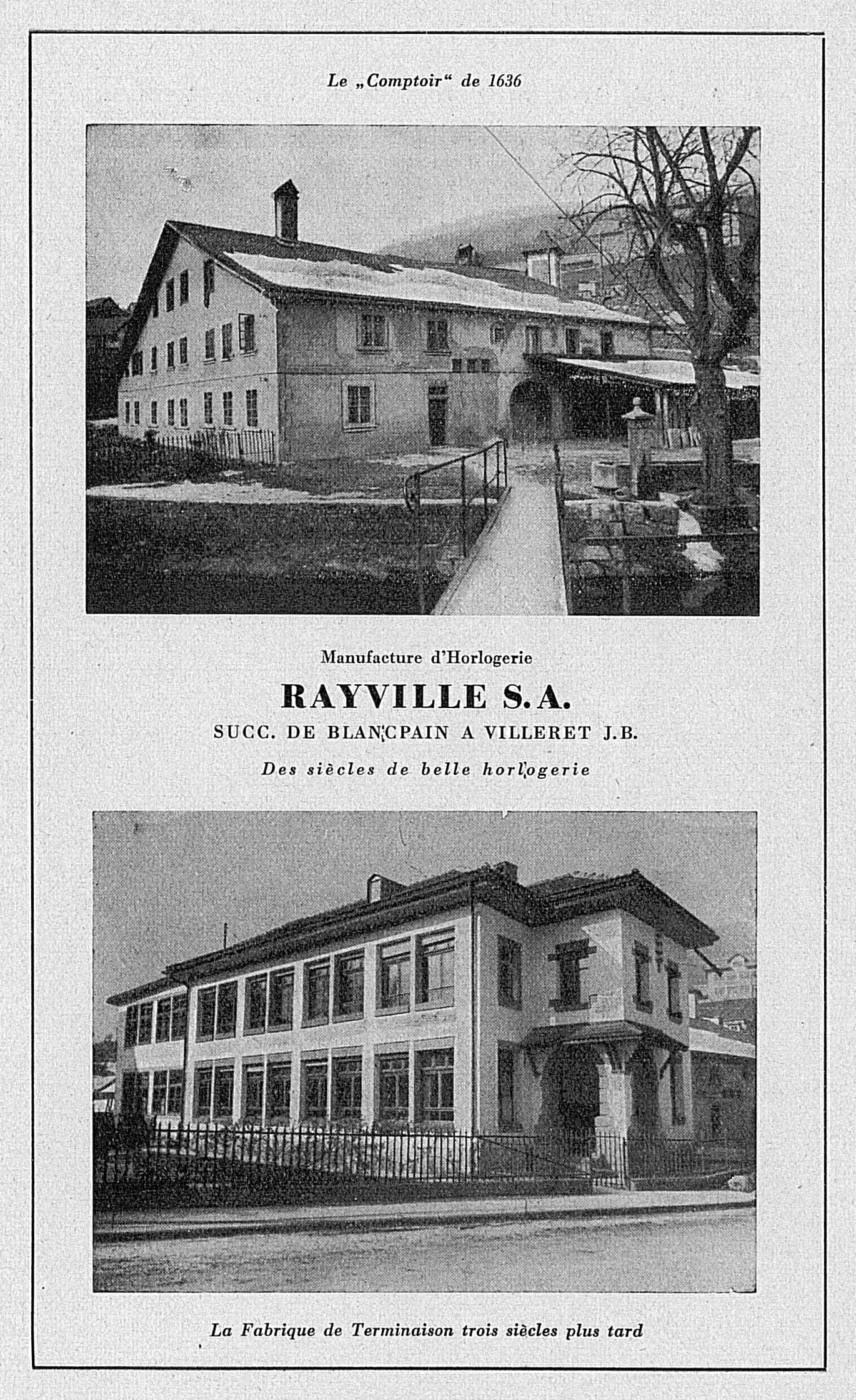

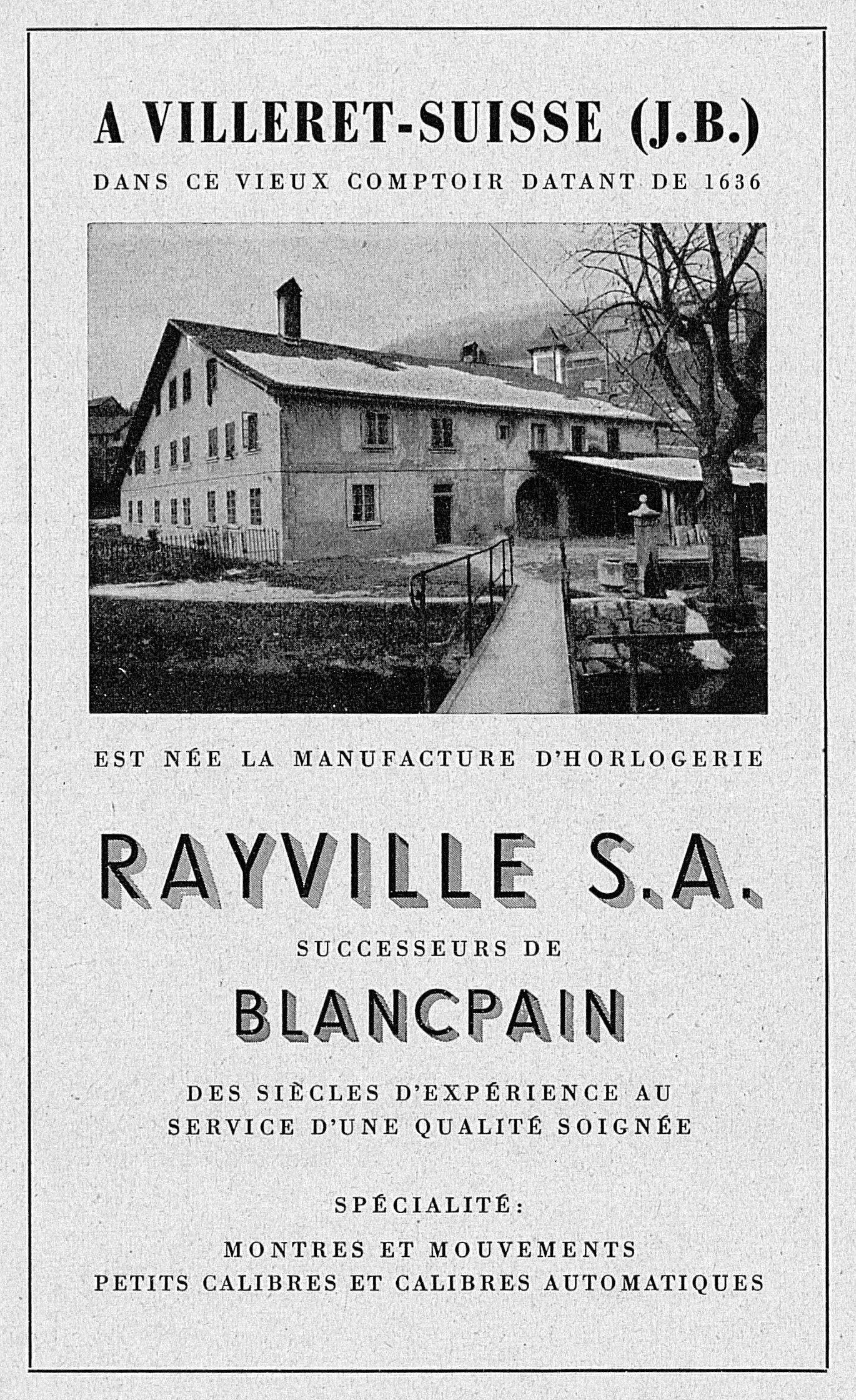

The 1636 house made its first appearance in the following Rayville ad published in the 1950 edition of Actes de la Société jurassienne d’émulation printed in 1951. The description “Le ‘Comptoir’ de 1636” is quite awkward as a comptoir was a counter or point of sales were watches were sold, often abroad (think of a retailer). In 1636 there was no watchmaking in the Jura and certainly no sales counter for watches in a tiny village with a few hundred souls. Whoever created this ad was only just learning about watchmaking history and probably confused comptoir with workshop.

In the 1951 edition of Actes de la Société jurassienne d’émulation printed in 1952, the comptoir story was elaborated.

.

“Dans ce vieux comptoir datant de 1636 est née la manufacture d’horlogerie Rayville S.A., successeurs de Blancpain. Des siècles d’expérience au service d’une qualité soignée.”

Translation: In this old counter, dating from 1636, the Rayville S.A. watchmaking factory, successors to Blancpain, was born. Centuries of experience at the service of neat quality.

Again, comptoir makes no sense in this context but here we can see the very beginnings of the what would later become the now established 1735 story. However, it was not until 1959 that the new narrative began to take a more concrete shape with the first mention of Jehan-Jacques Blancpain:

“BLANCPAIN, an old Swiss family name, has its origin lost in the shuffle of history. What we do know is that in 1735 Jehan-Jacques Blancpain, a wealthy farmer of the village of Villeret, constructed the first watches, and signed them with his name.”

Source: Blancpain advertisement, Europa Star Asia, 1959 (watchlibrary.org)

According to historian Dr. Marius Fallet (1876 – 1957), Jehan-Jacques’ father Isaac Blancpain was a master shoemaker:

“Nombreux furent parmi les Blancpain, les Charles, Grisard, Marchand et Renard les artisans du vêtement: cordonniers, tailleurs, etc. Depuis la Chandeleure 1687 à la Chandeleure 1690, Jacob Moucherand de Bienne a été l’apprenti du maître cordonnier Isaac Blancpain.”

Translation:

Many of the Blancpains, Charles, Grisards, Marchands and Renards were clothing artisans: shoemakers, tailors, etc. From Candlemas 1687 to Candlemas 1690, Jacob Moucherand from Bienne was the apprentice of master shoemaker Isaac Blancpain.

If the father was a master shoemaker, chances are Jehan-Jacques would have naturally followed in his footsteps. So how did Jehan-Jacques become a watchmaker? Where did he learn metalworking and ultimately watchmaking? According to both, Emile Bourquin and Dr. Marius Fallet, there were no watchmakers in Villeret in 1735. The first watchmaker in Villeret appears to have been Adam Bourquin, who was born in 1735 and opened his first workshop in 1758.

“Le premier horloger [a Villeret] y fut Adam Bourquin dit le Justicier, né le 20 octobre 1735.”

Translation:

The first watchmaker [in Villeret] was Adam Bourquin known as Le Justicier [a member of the local court], born October 20, 1735.

” A Villeret, c’est Adam Bourquin, dit le Justicier, qui fonde le premier atelier en 1758.”

Translation:

In Villeret, it was Adam Bourquin, known as the Justice, who founded the first workshop in 1758.

Interestingly, Jehan-Jacques Blancpain’s son Isaac, who was given the same name as his grandfather, the master shoemaker, was also born in 1735, just like Adam Bourquin. In light of this, the following advertisement run by Jean-Jacques Fiechter’s Rayville in the newspaper Journal du Jura on December 12, 1968 will make you chuckle.

“En 1735, alors qu’à Versailles la cour fastueuse et avide de nouveautés de Louis le Bien-Aimé [Louis XV] multipliait les amusements, à Villeret, village caché au creux d’une vallée du Jura suisse, Jehan-Jacques Blancpain et son fils Isaac se distrayaient de tout autre manière.

Dans leur vaste ferme construite en 1636, les longues soirées virent naître sous leurs doigts habiles leurs premières montres.”

Translation: In 1735, while in Versailles the lavish and novelty-hungry court of Louis the Beloved [Louis XV] was multiplying the amusements, in Villeret, a village hidden in the hollow of a valley of the Swiss Jura, Jehan-Jacques Blancpain and his son Isaac were having fun in a different way. In their vast farm built in 1636, the long evenings saw the birth of their first watches under their skillful fingers.

Source: Rayville ad, Journal du Jura, December 12, 1968 (e-newspaperarchives.ch)

Given that Isaac Blancpain was only born on August 8, 1735, one cannot help but wonder how much of a help the months-old baby could have been in building their first watches during the long evenings of 1735. The next passage of the ad is also quite interesting:

“Peu à peu, cet amusement devint passion, puis principale occupation et, un jour, le petit-fils de Jehan-Jacques, David-Louis Blancpain, aménagea un atelier dans la ferme familiale.”

Translation: Little by little, this amusement became a passion, then main a occupation, and, one day, Jehan-Jacques’ grandson, David-Louis Blancpain, set up a workshop inside the family farm.

Keep in mind this ad was the product of Jean-Jacques Fiechter, who was also a historian and novelist. The ad implies Jehan-Jacques’ watchmaking was more of a playful experimentation, and it was only David-Louis (1765 – 1816), Jehan-Jacques’ grandson, who built the watchmaking workshop on the first floor of the vast farm from 1636. The modern Blancpain brand, on the other hand, claims Jehan-Jacques built the workshop. This reminds me of the ever-changing Blancpain Fifty Fathoms narrative. On their 2012 website, Blancpain stated it was the French Navy that submitted the project to Rayville director Jean-Jacques Fiechter who agreed to built the watch. Today, Blancpain claims Fiechter had already developed the watch before the Navy came knocking and that the only contribution of the French was the antimagnetic cover. Of course this is all part of the fabricated claim that the Fifty Fathoms was the first modern dive watch since all documents point to 1954 as the year of creation and the Rolex Submariner was already in serial production in the second quarter of 1953. Clearly, there is a pattern here of changing the narrative to fit current storytelling.

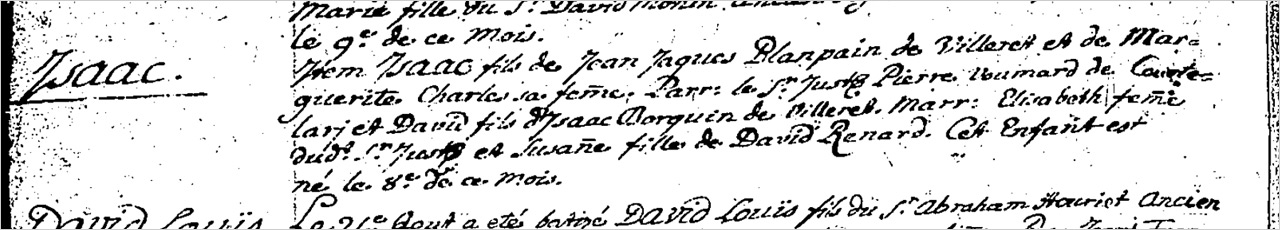

For this article, I went through the parish records (church registers) of St-Imier which are provided online by the State Archive of the Canton of Bern. In the baptism note for Isaac Blancpain, which can be seen below, his father Jehan-Jacques Blancpain was not listed as a watchmaker. Given he purportedly registered himself as a watchmaker in the same year, it sure is noteworthy that he did not do so when his son was born. Other men with extraordinary professions, and watchmaker would definitely count as such since he would have been the very first of its kind for miles around, can be found in 1735 listed with their careers, like, for instance, Abram Gagnebin on April 3, recorded as a surgeon (chirurgien), Abraham Houriet on October 4 as a master hatter (maître chapelier) and David Marchand as a cloutier (nail maker).

Source: Excerpt baptism register St-Imier from 1735 (State archive Canton of Bern)

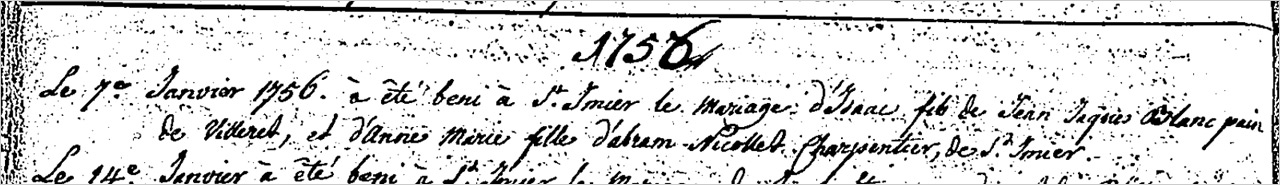

Furthermore, when Isaac married Anne Marie Nicollet on January 7, 1756, the father of the bride, Abram Nicollet, was recorded as carpenter (charpentier). Jehan-Jacques Blancpain’s profession on the other hand was not indicated which is strange for something as exceptional as a watchmaker in those very early days of watchmaking in the region. It sure looks like Jehan-Jacques was not very proud of his profession if he did not want it recorded for the history books.

Source: Excerpt marriage register St-Imier from 1956 (State archive Canton of Bern)

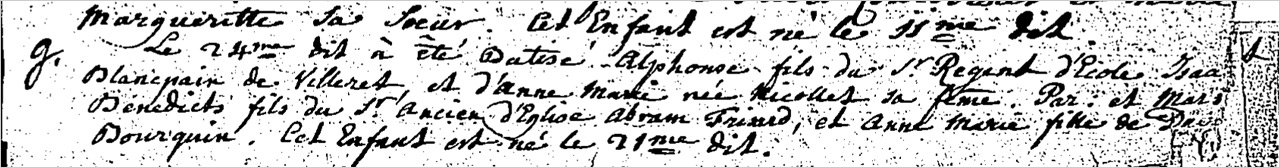

Isaac Blancpain went on to become the head of school (régent d’école) in Villeret. From 1768 onwards, as seen in the baptism record below of Isaac’s son Alphonse, most records where Isaac is mentioned list his profession next to his name.

Source: Excerpt baptism register St-Imier from 1768 (State archive Canton of Bern)

In his essay on the develpment of watchmaking in Villeret, Dr. Marius Fallet mentioned Jehan-Jacques and his son Isaac, the head of school (regent d’école). This makes clear Fallet conducted a thorough investigation into the Blancpain family. He went as far back as Jehan-Jacques’ father Isaac Blancpain, the master shoemaker (maître cordonnier) but could not find any indication of watchmaking in the family prior to Frédéric-Louis Blancpain. The valley of St-Imier is a small world. As the first watchmaker in the area, Jehan-Jacques Blancpain would have been a memorable figure.

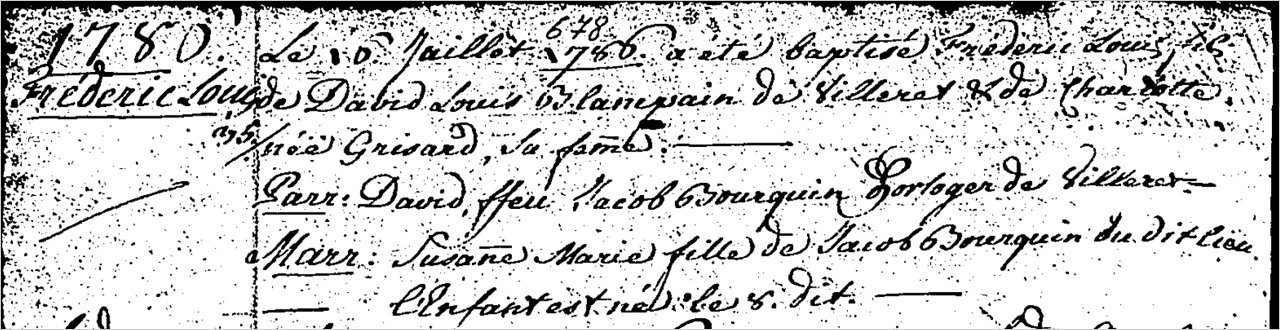

What about David-Louis, son of Isaac and grandson of Jehan-Jacques Blancpain, the guy who according to the 1968 Rayville ad set up the first workshop? Purportedly he was a watchmaker too, right? Below is the baptism record of David-Louis’ son, Frédéric-Louis Blancpain born on July 8, 1786. No profession next to David-Louis’ name which in this case is especially noteworthy as Frédéric-Louis’ godfather, David Bourquin, was listed as watchmaker (horloger). Now, David Bourquin’s father Jacob was the brother of Adam Bourquin, a.k.a. Le Justicier, the very first watchmaker in Villeret, according to Dr. Marius Fallet, remember? If David-Louis was also a watchmaker, why was it not mentioned in this record?

Source: Excerpt baptism register St-Imier from 1786 (State archive Canton of Bern)

David-Louis Blancpain had three other children. In none of the records, marriage included, was he ever listed as a watchmaker. After having gone through the available records over and over again, I could not find any indication that Jehan-Jacques, his son Isaac and his grandson David-Louis were watchmakers as claimed by the modern Blancpain brand. The first and only connection to watchmaking I found, although indirect, is the one above. Taking into consideration Dr. Fallet’s mentioning of David-Louis’ brother Frédéric Blancpain as being a horloger-établisseur in the late 18th century, this was probably the time the Blancpains made their first steps into watchmaking.

Coming back to the Rayville ad from 1968 which states Jehan-Jacques Blancpain was making watches with the help of his months old baby son Isaac during the long evenings of 1735, as you may have noticed, it makes reference to the vast farmhouse built in 1636.

“Dans leur vaste ferme construite en 1636, les longues soirées virent naître sous leurs doigts habiles leurs premières montres.”

Translation: In their vast farm built in 1636, the long evenings saw the birth of their first watches under their skillful fingers.

The 1636 Farm

The farm mentioned in the ad still exists today. According to Jeffrey Kingston’s article on the history of Blancpain published in Lettres du Brassus No. 5 in 2008, the building was erected in 1636 as a mail relay station:

“Remarkably, the building constructed in 1636, and originally purposed as a mail relay station, still stands today.”

Source: Lettres du Brassus, Issue 05, 2008 (PDF, blancpain.com)

This information is interesting as there are claims the Blancpain family built the house in 1636. As we also have seen, there are conflicting statements as to whom established the first watchmaking workshop on the upper floor of the farm. In 1968, Jean-Jacques Fiechter’s Rayville claimed it was David-Louis, Jehan-Jacques’ grandson. The modern Blancpain asserts it was Jehan-Jacques himself. To be clear, I have not found any evidence that Jehan-Jacques Blancpain lived in that house. Located next to the old Blancpain factory originally constructed around 1907 but rebuilt in 1963 following a fire, the two buildings are separated by the small river Suze. The photo below from 1936 depicting the farm and the Blancpain factory illustrates the vastness of the farm.

I reached out to Memoires d’ici, the Center for Research and Documentation of the Bernese Jura, seeking confirmation that the famous “Blancpain” farmhouse is indeed linked to the Blancpain family. Their database has several pictures of the farm from the 1930s, but interestingly only two are titled ‘Blancpain farm’. They told me the titles did not come from the original photographer. They themselves assigned the titles based on an article titled ‘The History of Blancpain’ published in the magazine Lettres du Brassus No. 5 in November 2008, a Blancpain publication. The article was written by Blancpain’s in-house historian Jeffrey Kingston. Basically, all claims linking the farm to Blancpain appear to originate either from Rayville or the modern Blancpain brand. The original Blancpain company founded in 1815 and operating until late 1932 never mentioned the farm.

In the following photo of the Blancpain watch factory from the early 1900s, the 1636 farmhouse can be seen in the background. There are a number of logs in front of the farm which could be an indication the building belonged to the sawmill nearby.

During my recent trip to Switzerland in June 2024, I visited the farmhouse at the Rue de la Gare 5 and was suprised to find a construction site. As it turned out, a fire on January 7, 2023, destroyed the upper two floors of the building almost completely.

For the past few years, the oldest house in Villeret was used as a residence building housing four appartments. Before that, it served for more than two decades as a Yoga University, with neighbours complaining it was the religious center of a sect. Following the fire, the private owner is rebuilding the structure as he pleases since it is not under any heritage protection. If you look closely at the picture below, which I took in June 2024, the upper level will be considerably higher, raising the roofline to about the height of the windows. Quite an intervention for a historic building if you ask me.

All of this is weird to say the least. Such an important site said to be the cradle of the “the oldest watch brand in the world” and it is neither owned/preserved by Blancpain nor protected by the Swiss authorities. The same applies to the old Blancpain/Rayville factory across the small river which has been transformed into an appartment building just recently. With the Swatch Group, it seems, it is all about storytelling. Heritage be damned!

Coming back to the 1735 story, Rayville appears to have never elaborated on the origins of that particular year and neither did the resurrected Blancpain brand under Jean-Claude Biver which was operational between 1983 and 1992. It was not until 2008 that the current Blancpain brand, since 1992 owned by the Swatch Group (SMH at the time), expanded on the issue. In the No. 4 issue of Blancpain’s Lettres du Brassus magazine from April 2008, on page 27, Blancpain said this:

In fact, this famous date marks the first written reference (in the Bishopric of Basel’s archives) to watchmaking activity linked with the Blancpain family name.

Source: Lettres du Brassus, Issue 04, 2008 (PDF, blancpain.com)

I searched the online inventories of the above mentioned archive for anything Blancpain with no success. Interestinlgy, after I questioned the veracity of Blancpain’s official history in September 2023, a guy named Benjamen Besson is now researching these archives on behalf of Blancpain. This is a fact mentioned in the archive’s 39th Annual Report of 2023 but more on this later.

In the No. 5 issue of Lettres du Brassus magazine from the same year, Jeffrey Kingston wrote the following:

“The citation to the 1735 date is grounded upon Jehan-Jacques recordation of his occupation as ‘horloger’ on an official property registry for the Villeret commune that year.”

Source: Lettres du Brassus, Issue 05, 2008 (PDF, blancpain.com)

In the Lettres du Brassus No. 17 from October 2016 we can read this from Mr. Kingston:

“When she [Betty Fiechter] joined, Blancpain was led by the seventh generation of the Blancpain family, Frédéric-Émile Blancpain who descended from the founder Jehan-Jacques Blancpain, who was recorded on the village rolls of Villeret as a watchmaker in 1735.”

In an official Blancpain video about the history of the Fifty Fathoms from 2021, the narrator said this:

“Villeret was the birth place of Blancpain, for in 1735, its founder Jehan-Jacques Blancpain was recognized on the official village rolls as a watchmaker.”

Source: The Fifty Fathoms History | Part One – Blancpain (youtube.com)

On their current website, Blancpain makes the following statement:

“Jehan-Jacques Blancpain registers himself as a watchmaker in the Villeret village records. He is the founder of the eponymous watch brand which will remain family-owned, handed down to his descendants, for almost 200 years.”

Source: History of Blancpain (blancpain.com)

These are conflicting statements. It is not clear whether Jehan-Jacques Blancpain was officially recognized as a watchmaker by an authoritative body or if he just wrote down that he was a watchmaker. The document in question has never been produced by the modern Blancpain brand, which is strange to say the least. Watch brands love to show off old records. Woah, woah, woah, hold your horses Perez! Didn’t Blancpain publish something in the history section of their website that resembles an ancient signature? Sure, the thing you see below. For starters, it is standing on its own which is awkward as it would be part of something larger. Furthermore, if you know 18th century signatures, this is clearly off. Also, the spelling is wrong as certain words in 18th century French were often written differently.

The mystery surrounding this image is easily solved. It was created as part of a short video in 2015. The question is, if there is a real record, why present this fake thing instead?

At this point it also needs to be said that registering oneself as a watchmaker does not really equate with founding a watch brand, at least not in my book. In all fairness, Rayville never claimed that, they merely said “Watchmakers in Villeret since 1735”. It is the modern Blancpain brand that went completely overboard with storytelling. Regardless, if we look at Vacheron Constantin which was considered the oldest watch brand in the world before Blancpain started claiming to throne for themselves, its founding date of 1755 relates to the date stated on an apprenticeship contract, making clear Jean-Marc Vacheron was a master watchmaker with employees, the beginning of a company if you will. It is interesting to note that Vacheron Constantin’s founding date used to be 1785, the year the company’s archives can be traced back to but in 1952, the aforementioned contract was discovered and the founding date was adjusted accordingly, making Vacheron Constantin even older than Breguet (1775).

Now, Vacheron’s claim is based on real tangible evidence. In comparison, Blancpain’s claim is not on the same level, not even close. Also, there are conflicting statements as to whether Jehan-Jacques Blancpain was officially recognized as a watchmaker by an authority or if he registered himself as a watchmaker. But then again, the guy was neither mentioned by any of the researchers who studied the history of watchmaking in the Jura nor by the Blancpain family itself. Not sure how all of this could ever pass the sniff test and be widely accepted but then again, all so-called watch journalists are comfortably nested in the big pockets of the mighty Swatch Group. An interesting observation is also that Jean-Jacques Fiechter started playing around with the history of Blancpain right after Vacheron Constantin updated their founding year. Coincidence? Anyway, since Blancpain never showed the 1735 record in public, I reached out to the village council of Villeret and asked for it. This was their reply:

“Nous avons déjà cherché à de nombreuses reprises, mais nous n’avons pas ce document. L’entreprise Blancpain Montres nous a déjà aussi demandé ce document, malheureusement sans succès.”

Translation: We have already searched many times, but we do not have this document. The company Blancpain Montres has already requested this document from us, unfortunately without success.

The village council’s reply was no surprise. Having studied Blancpain’s history for some time now, including a deep dive into the Fifty Fathoms “first modern dive watch” narrative which fails to hold water under superficial scrutiny, I was expecting exactly that. Not only does the village of Villeret not have said record, Blancpain is fully aware of the fact as they have been asking for it themselves. To give Blancpain the benefit of the doubt, I reached out via email to the brand’s in-house historian Jeffrey Kingston, confronting him with Villeret’s statement and requesting a picture of the 1735 record he so eloquently gushed about in his many publications about Blancpain. There was no answer. I also reached out to Blancpain, twice, via web contact form but there was no answer either. Yesterday after four long weeks of radio silence, Blancpain’s Head of Marketing Alexios Kitsopoulos sent me an email. Not to provide the 1735 record as previously requested, but to soft-soap me via a proposed tasty lucheon date to “better understand my motivation”. It seems people just cannot grasp when others are not motivated by money but solely by the pursuit of truth.

As mentioned earlier, Blancpain has now hired a certain Benjamin Besson to go through the Archives of the former Bishopric of Basel, probably in search for the mysterious 1735 document. Form 1264 to 1815, the Bernese Jura was part of the Erguël seigniory of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Basel, named after the first governor Otto von Erguel. Many of the regional documents concerning the 18th century can be found there. Fun fact, I reached out to the Archives of the former Bishopric of Basel to see if they could share any new discoveries related to Blancpain and if they could connect me to Mr. Besson. There was no answer. Eventually, I found Mr. Besson on LinkedIn and sent him an invitation to connect. He immediately blocked me.

Is it not interesting that Blancpain mentioned these archives back in 2008 but it appears they are looking into it only now, 16 years later? It sure makes the impression the modern Blancpain never saw the record nor had they ever a copy of it to begin with and after I called them out, they are now scrambling to find it. If true, Blancpain has been claiming to be oldest watch brand in the world without any evidence, based solely on Jean-Jacques Fiechter’s alteration of the Blancpain history in the mid 1950s. I truly hope they find something because if not, legitimate questions like whether the whole story was made-up out of whole cloth by the brand’s revered former director Jean-Jacques Fiechter will have to be asked. You know, the same individual who claimed to have invented the first modern dive watch…

The implications would be wild. Fiechter wrote several books as a historian, and all of his output would have to be taken with a truckload of salt. Furthermore, Fiechter was involved with the modern Blancpain brand since 2002, which is interesting as the Blancpain Fifty Fathoms narrative, as mentioned earlier, changed several times over the past two decades.

“Since 2002, he has held a place of his own within Blancpain. The arrival of Marc A. Hayek at the head of our Manufacture enabled two parallel destinies to intersect. Jean-Jacques Fiechter found in Mr. Hayek a ‘soul mate’ with whom he had much in common. He notably witnessed the rebirth of the Fifty Fathoms under the impetus of Mr. Hayek, driven by a passion for diving and the oceans like his own.”

Source: Tribute to our esteemed friend Jean-Jacques Fiechter (blancpain.com)

If Fiechter was indeed Blancpain CEO Marc A. Hayek’s “soul mate”, how does the latter explain the ever changing story?

Thoughts

If Blancpain wants to keep boasting about being the oldest watch brand in the world, they better produce the 1735 record. If they care about their credibility that is. Having said that, I am fairly certain there never was such a record to begin with. The “tale”, as Jeffrey Kingston fittingly kicked off his article on the ‘History of Blancpain’ in Lettres du Brassus No. 5 from 2008, has all hallmarks of a complete fabrication. As researchers like Bourquin and Dr. Fallet asserted in the past and all of today’s available data indicates, this branch of the Blancpain family’s history in watchmaking began with Frédéric-Louis Blancpain (1786 – 1843) in 1815. Still a very early date and something to be proud of, just to be clear.

The throne of the oldest watch brand in the world belongs to Vacheron Constantin in my opinion, regardless of whether Blancpain can come up with the 1735 record or not. There should be a standard as to what can be considered the birth of a watch brand. Registering oneself as a watchmaker in the village rolls (did they still use rolls in 1735, really?) is not on the same level as being a qualified master watchmaker officially certified to train an apprentice, not even close. In addition, Vacheron, and Breguet for that matter, were horological powerhouses from the very beginning. What can Blancpain present in this regard? Not much. Heck, they only started making moon phases in 1983 when the lifeless brand was resurrected as something it never was, a luxury watchmaker. Why was Blancpain graded on a curve all this while? Why did the mainstream watch media not ask the tough questions? Ah right, they were being wined and dined at exclusive locations by the Swatch Group. “Living the dream”, as one of the whore-ological leeches perfectly put it on his Instagram profile. Imagine dreaming of living a life on your knees, gleefully sucking up to watch brands.

If you care about this matter and are also eager to see the original 1735 record, please contact Blancpain via web form and social media channels and demand they produce it. Thank you for your interest.

Read more: Debunking the fictitious history of the Blancpain Fifty Fathoms

birth and development of watchmaking in Villeret, by Dr. Marius Fallet, 1937

- La Fédéreration Horlogère Suisse, ‘Naissance et développement de l’horlogerie à Villeret’, No. 44, November 3, 1937 (5.7 MB)

- La Fédéreration Horlogère Suisse, ‘Naissance et développement de l’horlogerie à Villeret’, No. 45, November 10, 1937 (PDF, 5.5 MB)

- La Fédéreration Horlogère Suisse, ‘Naissance et développement de l’horlogerie à Villeret’, No. 46, November 17, 1937 (PDF, 5 MB)

Update August 30, 2024

Before hitting the publish button for this article, I came across the information that Favre Leuba is very old too. There is an apprenticeship contract of young Abraham Favre dating from 1718, and according to the brand, Favre was officially recorded as watchmaker in Le Locle in 1737. However, Favre was trained by watchmaker Daniel Gagnebin (1697 – 1735), and the Gagnebin&Cie brand exists to this day, making it even older than Favre Leuba. Looks like I will have to go down this new rabbit hole next. There go another three months of my life.

A very special thank you to Rossella Baldi for her precious help in guiding me to the parish records of St-Imier and through 18th century life, words and practices, going for me into the regional archives, and providing the manuscripts and publications of Emile Bourquin and Dr. Marius Fallet. Rossella is a Project Manager at the University of Neuchâtel, a historian specializing in 18th – 19th century horology and an ex-curator of the Musée international d’horlogerie in La-Chaux-de-Fonds.

Großartig, wieder ein neuer Krimi. Ich habe es verschlungen und ich feier Dich

LikeLike

As always excellent essay Jose! As a matter of general update I posted in the WUS thread entitled “Comeback of the year? The return of the oldest watch brand in the world , Favre Leuba “.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing this research.

LikeLike

Brilliant as ever Jose. Thank you for your work.

LikeLike

Although I was never particularly interested in Blancpain, I found this excellently researched article very worth reading. It reminds us that marketing is allowed exaggerate but should never lie. Unfortunately, Blancpain clearly exceeded this limit of what is legitimate. Beside other interesting historical facts, I also had to learn that the masses of bored mountain farmers who once made watch parts in the winter never existed. It is easy to believe lies when they are plausible. Too easy, I guess… Thank you José!

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

Unfortunately, well-researched and thorough articles on mechanical timepieces and the watch industry are becoming increasingly rare these days. Thank you very much for your excellent work—please keep it up!

BR,

Omar

LikeLike

Same story with Breitling. The company folded in 1979 because the family lost interest in making watches. Sinn bought the tooling along with all parts in production. Later, Secura bought the name and stopped producing watches under the name of Secura. A few years ago CVC Capital Partners (private equity) bought the company. The Breitling website boasts a history going back over a century. Go figure.

Thanks for the article. I was alerted to the article via Instagram.

LikeLike

As nazi german chef of propaganda Goebbels said: “a lie told a thousand times becomes the truth”. Isn’t it the case with all those watch reporters? They are just living on a hype, repeating what they have heard from older collegues and brands official statements. No actuall work is dobe here, no investigation like yours. Why? Are they really deep in the pockets of watchbrands? I dont know but it is easy to believe that they are suckers as we all are. Like the story about bored farmers creating watches during the winter. It was always a romantic fairy tale but yet everyone repeat it as a fact in multiple sources. Go figure…

LikeLike

Great read as always, thank you

LikeLike

Great research work, congratulations for debunking Blancpain ! One subtelty in French though, in the list of ads you published the 1st time 1735 is mentioned they wrote “dès 1735”. “Dès” does not exactly translate into since (which would rather be “depuis”), dès stands more for “As early as”, which in Blancpain’s narrative could be correct (I am not saying it is), but if you accept the idea that Jehan-Jacques was a watchmaker in Villeret as early as 1735, it could eventually stand; or at least it is almost correct !

LikeLike

Pretty cringe of Blancpain. I still like they’re watches, but this is a good lesson in the bullshit that watchbands sell.

LikeLike

Very well put questions, bravissimo! I’ve always wondered why I’ve never seen an antique Blancpain watch from the 18th and 19th centuries in an auction catalog. The only Blancpains I’ve seen were watches from the 1920s and later (but much earlier compared to FF), that time Blancpain watches definitely appeared on a market. Back then, the brand specialized in small ladies’ watches and supplied other brands, including Eszecha (then owned by the Scheufeles, who now run Chopard). At the same time, Blancpain also collaborated with Leon Hatot in the development (probably) and production of his Rolls watches.

LikeLike

Blancpain did not actually start signing its watches until the 1920s. Before that, the family used a multitude of different names. They are only identifiable when the lion, the emblem of the family, is stamped (Source: commercial register).

LikeLike

Great idea to also focus on Favre-Leuba. While you’re at it why not also look into Haldimann who claim to be the oldest watch brand, having started in 1642.

LikeLike

Gallet & Co claim to have been continuously in business since 1466

LikeLike

Congrats!

LikeLike

There is a reference by Time and Watches to the property registry of the Villeret municipality where there reportedly is a record in 1735 in which Jehan-Jacques Blancpain is indicated as “horloger”.

LikeLike

Yes, the are many variations of this story. Fact is, the original record has never been produced. Instead, Blancpain shows a fake “record” on their website.

LikeLike

When it comes to the Swatch Group in general and Blancpain in particular, nothing surprises me any more. I can only report bad experiences – up to and including legal action. With your enthusiasm, perhaps you could also address the following issue: Blancpain suggests that all its watches are assembled in the Vallée de Joux, but in fact a significant proportion of its timepieces are probably assembled in a production facility belonging to another Swatch Group company in the canton of Ticino.

It is – to put it mildly – audacious to explicitly claim on its own website, without any proof, that Jehan-Jacques Blancpain registered as a watchmaker in the village of Villeret in 1735 and that he was the founder of the company of the same name, which remained in the hands of his family through his descendants for almost 200 years.

LikeLike

What do you think about Badollet ? It is said to have been founded in 1635.

https://www.badollet.com/

LikeLike

Exceptional article. Apparently Baloney is a widespread delicacy in our modern civilized world.

Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

Bravo pour ce fantastique travail de recherche sur le village de Villeret, la famille Blancpain et ses premiers horlogers. Cordiales salutations Yann Bourquin Rue de la Gare 32 à 2616 Villeret / Suisse

LikeLike

This opens an opprtunity for a class action lawsuit and possible action by the NY State Attorney Generals Office.

LikeLike

This article is balm for my soul.

The history of Swiss watch brands is full of pure marketing stories that are devoid of any truth.

The press in Switzerland is dependent on the advertising of the watch brands and nobody dares to tell the truth.

Thank you Jose for your article, I know how much work and effort went into it.

LikeLike

Excellent, thank you for your work.

LikeLike

What about Perrelet, who claim to be the “inventor of the automatic watch” and in business since 1777?

LikeLike