Rolex just launched their first authorized book on the history of the Rolex Submariner based on actual archive material. Watch enthusiasts who have been craving official information for a long, long time, will love some of the genuinely amazing stories, which confirm to a large extent what we researchers have written in the past. However, once the first previews were out, something else became clear. The book makes false claims and is riddled with errors. Authored by watch establishment hack Nicholas Foulkes, who is totally out of touch with the world of Rolex collecting, it comes as no surprise the new publication perpetuates the long-debunked claim that the Rolex Oyster from 1926 was “the first waterproof wristwatch in the world”. Rolex did not invent the waterproof wristwatch, they perfected it. In 2024, it is time for brands to drop these annoying marketing exaggerations from the past and start talking about actual history. For vintage Rolex collectors expecting answers to so many burning questions, the new book is not worth the paper it is printed on. Strap in, as there is a lot to unpack.

The Corpus Delicti

The following is an excerpt from page 92 of the authorized Rolex Submariner book, showing the timeline 1922 – 1953. The 1926 Rolex Oyster is clearly described as something it was not:

“…the Oyster was the world’s first waterproof wristwatch…”

The false claim was also made on page 16 (low resolution preview) where is says:

“The Oyster, the first waterproof wristwatch in the world, was launched in 1926.”

Continue reading for more errors or click here to go straight to the debunking of the fictitious history of the 1926 Rolex Oyster being the first waterproof wristwatch in the world.

In addition to this outrageous claim, Mr. Foulkes made it look like the 1922 Rolex Submarine, a case-in-case concept patented and produced by Jean Finger (Patent CH87276), which was also used by other watch brands, was a Rolex invention. It was not. On page 43, Foulkes, who refers to himself as a historian, wrote it was the best that could be done in 1922, completely ignoring horological history, as you will see further ahead. The official name of this case was ‘Double Boitier Hermetique’ (hermetic double case).

Source: Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie, December 1921, page 384 (watchlibrary.org)

Furthermore, the Rolex Submariner shown in the timeline is actually a second generation model. One would expect to see the earliest version presented at the Basel Watch Fair in May 1954, as depicted in the picture below. The difference lies in the dial, how the words Oyster Perpetual are arranged underneath the Rolex logo. Also note how the so-called lollipop seconds hand has a much larger luminous dot.

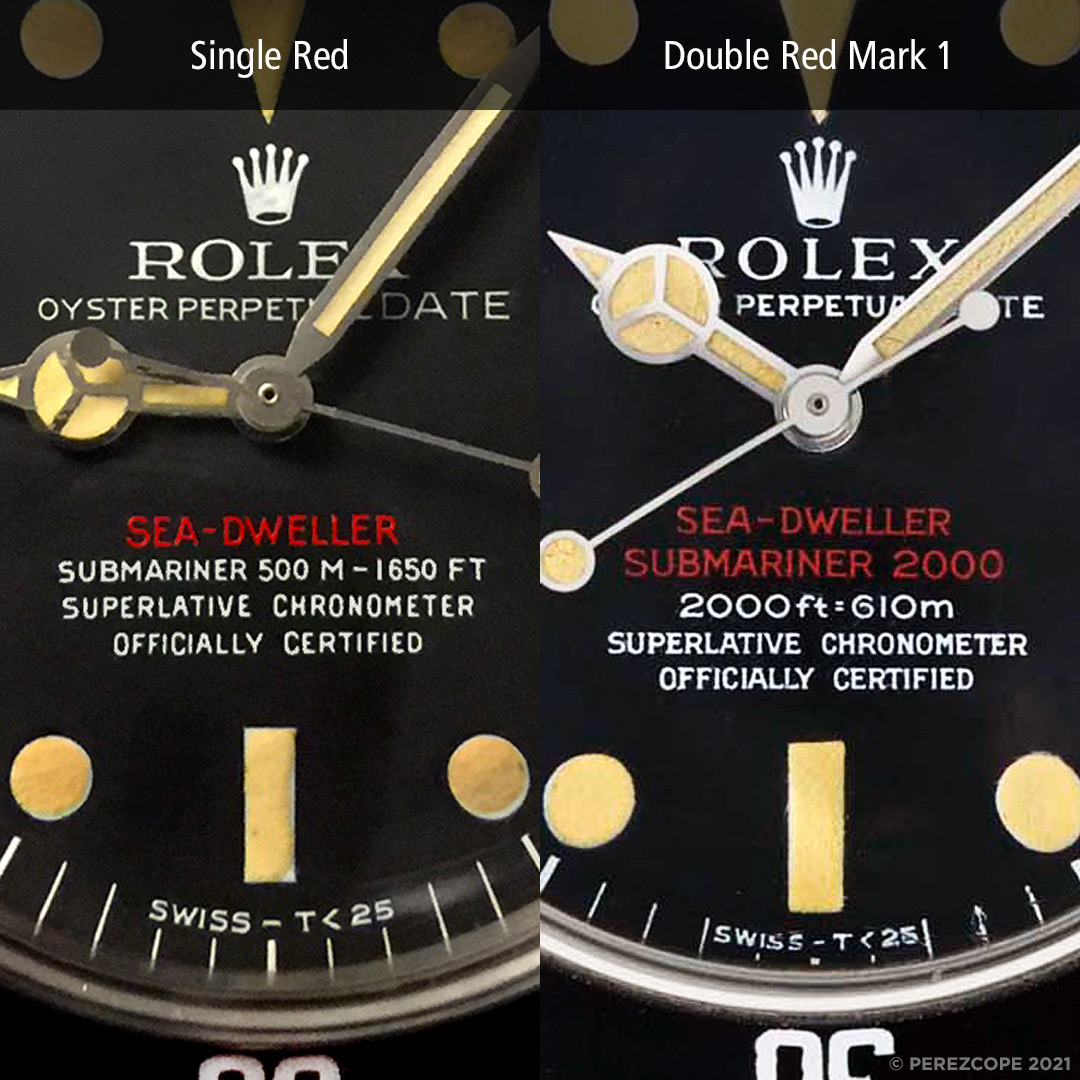

Sure, these are minute details but is that not what vintage Rolex collecting is all about? Author Nicholas Foulkes does not seem to have a deeper understanding for this fact. The following is also a massive blunder. There was no ‘Double Red’ Sea-Dweller in 1967. It was launched as a testing prototype in 1969 (Mk 1) and became available to the public only in mid 1970 (Mk1/2). The watch shown in the timeline is a ‘Double Red’ Sea-Dweller Mk2 from mid 1970 onwards.

The earliest Sea-Dweller model, produced in the second quarter of 1967, was the so-called ‘Single Red’ with a depth rating of 500 m/1650 ft. None of the around 50 pieces made had a helium release valve initially as the valve concept had not reached Rolex yet.

The one-way valve was an idea of U.S. Navy SEALAB Aquanaut Bob Barth, but a diver named T. Walker Lloyd brought it to Rolex’s attention, who was rewarded by Genevean company with a specially created job as oceanographic consultant. Neither Barth nor Lloyd are mentioned in the book, which is weird to say the least, especially since T. Walker Lloyd was immortilized in a 1974 Rolex Sea-Dweller advertisement as having kept in touch with the development of the valve since its conception.

The following picture shows the very first valve prototype made in early 1968, before some of the 50 initial examples were retrofitted with the valve. This watch was specifically made to be tested in a spectacular experiment called ‘Hydra’, conducted by the emerging French commercial diving company Comex. For the first time ever, highly flammable hydrogen was used as breathing gas. Just look at the amazing ‘Bart Simpson’ coronet on the ‘Single Red’ dial. I bet Nicholas Foulkes has never heard of this nickname before.

I have yet to see the entire book. Still, I know that the story of the first valve prototype is completely missing,. The watch was given to leading hyperbaric researcher Dr. Werner Brauer, who was investigating the high-pressure nervous syndrome and came up with the concept of using hydrogen to overcome it. You can read all about it in the following two articles which I wrote during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Read more: The Sea-Dweller Chronicles – Genesis of the decompressing watch

Read more: The Sea-Dweller Chronicles – Dry run and teaming up with COMEX

Speaking of Comex, on page 86, Nicholas Foulkes stated that Comex devised the concept whereby saturation divers do not live in underwater habitats as in SEALAB but return in pressurized diving bells to comfortable hyperbaric chambers on the surface after their work is done for the day. This concept was actually introduced by the underseas division of Westinghouse Electric Corp. in the United States. Named ‘Cachalot’, the first ever commercial saturation dive with this concept took place in September 1965. Comex launched their own system ‘Idefix’ in early 1967. Seriously, what kind of historian is Mr. Foulkes?

Rolex and Comex teamed up in late 1971. Before that, Comex had been collaborating since 1968 with Omega to create the ultimate professional saturation diving tool watch, which resulted in the Omega Seamaster 600 ‘PloProf’, a watch so well-engineered, it did not require a helium release valve. You see, the valve was more of a quick fix that saved Rolex from having to invest in the development of a completely new model.

Source: 8 days at a depth of 830 feet with a ‘Seamaster 600’, Europa Star, 1971 (watchlibrary.org)

Comex was not quite happy with the bulky design of the Seamaster 600, as it did not go easily unter the sleeve during leisure time. The story of how Rolex prevailed over Omega is quite interesting and best recounted by Comex founder Henri Delauze himself.

“One day Mr. Heiniger [Director of Rolex] … he proposed to give me 100 watches that will be called Rolex-Comex for free that we will give to 100 deep divers, … and everytime we have to repair one, we were supposed, and we did, send the watches to Geneva so that we have a good knowledge of what were the fragile points of the watches, and then nearly every two years they give us 200 more Rolex-Comex. … I knew Omega before Rolex and I abandoned Omega immediately when he bring me 100 new watches.”

Source: Interview with Henri Delauze from 2009 conducted by Jake Ehrlich of RolexMagazine.com

In the book, you will search in vain for why and when Comex and Rolex started working together. The whole story is deliberately vague, even kind of suggesting that the helium release valve was developed with Comex, which is absolutely not true. There are more errors related to Comex. In the chapter ‘Submariner – Evolution of an Icon’ (pages 236 – 241), which is an overview of all Submariner models made, the launch year of Ref. 5514, a regular Submariner with helium release valve specifically made for Comex, is stated as 1969. Ref. 5514 was introduced in 1974. The indicated production quantity of 1,618 pieces is way to high. My database’s estimate is around 800 pieces related to Comex. For a company operating within tolerances of one hundredth of a millimetre, all of this is awefully imprecise. In addition to errors, this chapter has also lots of missing models, Ref. 168000 for instance, a model which marked the transition from 306L to 904L steel. Missing are also Ref. 6538 A and Ref. 6540 (A/6538), two very important Submariner models made for the British Navy. Rolex acknowledged their existence in the past so why are they not in the book? Another model you will search in vain is Ref. 6536/1. They mention Ref. 6536 with 5,350 pieces made but that is impossible as only about 400 examples were made. The 6536 has a thicker case than the 6536/1. It’s a different model altogether. The numbers of these two models were probably combined but based on my own research, they produced only around half the quantity.

This is the first time Rolex disclosed production numbers, which is great. However, from a collector’s perspective, these numbers are practically useless in the form provided in the book and here is why. Knowing that a total of 22,038 Sea-Dweller Ref. 1665 watches were made is more or less irrelevant. Collectors want to know how many of them were Single Red, how many Double Red Mk1, Mk2, et cetera, et cetera. Surely they will also want to have an answer as to what the following super rare dial is all about, the so-called Mk0, some of which were found on non-valve Sea-Dwellers assembled in 1971. Why were there non-valve Sea-Dwellers in 1971 to begin with?

The same applies to the Submariner Ref. 1680 with its six ‘Red’ and four ‘White’ dial variants. What collectors are craving for is detailed information. In this regard also, the new book is disappointing. Thanks to my extensive database with currently more than 100,000 well-documented watches, I can easily tell how many of each type were approximately made. One would think Rolex has much better data at hand, but how is it possible then that on page 163, they show the following picture of a Ref. 5512 Submariner, claiming it is from 1959?

The watch in the picture has a ‘Pointed’ crown guard and clearly a so-called ‘Underline’ dial. It is not from 1959 but from 1963, shortly before the introduction of tritium designated dials (Swiss vs. Swiss – T <25). In addition, it is riddled with service parts like the crystal, the bezel insert (see pearl) and the clasp (6251H), which belongs to a Jubilee bracelet if I am not mistaken. The earliest 5512s had so-called ‘Square’ crown guards, followed by the ‘Eagle Beak’ type.

What is also wild, now that we know underwater photographer Dimitri Rebikoff was a leading force behind the development of the Submariner, is that there is no picture of him wearing one in the book. Rolex and the author seem to be completely detached and out of touch with the discoveries made by the watch community, else they would have been aware of the following picture of Rebikoff unearthed by horological eagle-eye Nick Gould (IG: @niccoloy) some time ago.

To conclude, these are the incorrect claims and errors I spotted in the book previews. There are probably many more. Things like this happen when a fancy word juggler like Foulkes, who has never studied vintage Rolex, works on such a project in his quiet little chamber. Eager for the laurels, it never even crossed his mind to reach out to knowledgeable collectors and scholars. Breitling has shown how authorized books ought to be conceived. From the very beginning, they worked with top Breitling collector Fred Mandelbaum (IG: @watchfred) to make sure the information provided is correct and usefull.

The First Waterproof Wristwatch

There were several waterproof watches before the Rolex Oyster came along in 1926. Waterproof pocket watches were known since at least 1851, according to watch expert David Boettcher, who has researched this topic to exhaustion.

1911 – F. Borgel

The first waterproof wristwatch cases appear to have been offered by Swiss casemaker F. Borgel in 1911. Borgel was working on waterproofness since at least 1891 when he patented his first water resistant case. An improved case consisting of three pieces was patented in 1903. In the following advertisement from 1911, they started offering wristwatch cases as well, on special demand from car drivers and members of the British army and colonies (bottom, right).

The 3-piece case is of special interest as it is almost identical to the Rolex Oyster case from 1926.

“Nouvelle Boîte impermeable à vis en 3 pièces… Cette nouvelle boîte à vis, hermetique, est formée de trois pièces; soit la lunette, le fond et la carrure se vissant toutes trois sure le garde-poussière, dans lequel est ajusté le mouvement. Les fermetures sont hermétiques et la boîte très solide, par le fait que le garde-poussière appuie de chaque côté, dans le fond et dans la lunette de glace, une fois ces pièces vissées.”

Translation: New 3-piece waterproof screw case… This new airtight screw case is made up of three parts; the bezel, the caseback and the middle case all three screw onto the dust guard [movement retaining ring], in which the movement is placed. These closures are airtight and the case is very solid, by the fact that the dust guard [movement retaining ring] presses on each side, against the caseback and the bezel with the glass, once these parts are screwed in.

Source: Revue internationale d’horlogerie, 1911 (watchlibrary.org)

From what I understand, these Borgel cases did not have any gaskets. The metal-to-metal joints were so smooth and precise, sealing materials were not necessary. There is a story from March 1915 about an early Borgel pocket watch that was lost in the Modder river in South Africa during the Second Boer War (1899 – 1902) and reportedly survived several days submerged in water. These were by no means diving watches but they were waterproof and could withstand water intrusion to a practical extent. The main objective was to protect the movement from humidity and dust.

The Rolex Oyster case from 1926, available in two shapes, octagonal and cushion, was heavily inspired by Borgel’s 3-piece case construction from 1903, as can be seen in the exploded view below.

The major break through of the Oyster case was the screw-down crown, an idea which Hans Wilsdorf acquired from its inventors Paul Perregaux and Georges Perret (Patent CH114948, filed October 1925).

1915 – Tavannes ‘Submarine’

In late 1915, in the middle of World War 1, the Swiss watch manufacturer Tavannes created a waterproof wristwatch named ‘Submarine’, around 35 mm in diameter and offered exclusively by Brook & Son Jewellers in Edinburgh, Scotland.

The story goes, as reported in the British Horological Journal in December 1917, that two off-duty submarine commanders approached Brook & Son to commission a special watch which not only needed to be absolutely waterproof but also non-magnetic, impervious to temperature fluctuations and highly visible in the dark. The case of the ‘Submarine’ is similar in principle to F. Borgel’s 3-piece case but simpler in construction as the movement is fixed directly to the middle case, thus not requiring a separate movement retaining ring. Bezel and caseback had a recess where greased sealing material was filled. The crown tube had an oiled leather gasket held in place by a screwed brass nut.

Not much is known about the development of the Tavannes ‘Submarine’. The inside of the caseback has a ‘Brevet +’ stamp, which refers to a Swiss patent, but the corresponding document has not been found yet. Brook & Son advertised the ‘Submarine’ as “the first waterproof wrist watch made”, which, given its construction and the use of sealing materials, is absolutely credible.

1918 – Depollier

Of special importance when it comes to early waterproof watches is the Depollier Waterproof Watch developed by Jaques Depollier & Son in the United States, and more importantly, extensively tested by the U.S. government in 1918 and proven waterproof.

Originally powered by a Waltham movement, the United States Army Signal Corps division placed an order of 10,000 cases in December 1918 to use with their own standard movements (Elgin, Illinois). The following advertisement from September 1920, published in The Keystone jewelry trade magazine, shows how the watches were tested in a lockable water tank.

Below is an excerpt from the Annual Report of the Chief Signal Officer to the Secretary of War, dated June 30, 1919, making reference to the waterproof cases:

“After examining many designs the engineers of this section finally adopted a design of waterproof case in which a watch could actually run for several weeks under water. The bezel in this case is tightly screwed against an oil-filled washer, thus making an impervious seal. The pendant is provided with a locking cap which seals all openings at this point. Many thousand of these cases were ordered, and it was contemplated to put the standard Signal Corps watch movements into them. This was being done when the armistice was signed. Several satisfactory movements had also been examined, tested, and accepted by this section.”

Depollier’s waterproof watch was also discussed in the Swiss watch media in an article from 1919:

“Les montres Depollier imperméables sont soumises aux observations les plus rigoureuses. La boîte est d’abord essayée seule, pour vérifier son imperméabilité à l’eau et à la poussière, puis la montre complète est immergée dans un réservoir ou elle marche pendant un certain temps sans observation.”

Translation: Depollier waterproof watches are subject to the most rigorous observations. The case is first tested on its own, to check its impermeability to water and dust, then the complete watch is immersed in a tank where it runs for a certain time without observation.

Source: La montre imperméable Depollier, Revue internationale de l’horlogerie, 1919 (watchlibrary.org)

The fascinating saga of the Depollier Waterproof Watch was almost lost in the shuffle of history. Thanks to Stan Czubernat, who did an excellent and award-winning job at chronicling this critical chapter of horological history, Depollier is the ultimate testament to the fact that the Rolex Oyster was not the world’s first waterproof wristwatch.

Read more: Waltham Depollier Waterproof Watch (lrfantiquewatches.com)

“Historian” Nicholas Foulkes has done a terrible job on this subject. He should be ashamed of himself. Continue reading to learn more about the Rolex Oyster from 1926 and how the outdated design lived on in the first professional diving tool watches made by Rolex for the Royal Italian Navy during World War 2, a dark chapter that was completely skipped over in the book, or click here for my final thoughts on the matter.

The Rolex Oyster from 1926

Latest research suggests that among the first Rolex Oyster models produced, were some Oyster pocket watches made between October 1925 and Mai 1926 while the patent application for the Perregaux and Perret screw-down crown (CH114948), the very invention which made the Oyster possible, was still pending. Evidence for this are the stamps ‘Patent applied for +114948’ found on the casebacks of all known examples.

These elegant timepieces are extremely rare. If you ever come across one in your life you can consider yourself lucky. In late 2022, I had the chance to inspect not one but three of them during a trip to Taiwan. They are absolutely gorgeous!

Basically a 3-piece F. Borgel case, the real innovation of the Oyster lied in the screw-down crown invented by Perregaux and Perret in 1925. Hans Wilsdorf quickly realized its potential and acquired the patent. The problem with this first design was that the stem remained engaged when screwing down the crown. Especially when fully wound, this operation put enormous stress on all parts involved, even to the extent of damaging the mainspring. To avoid the issue, a new patent was filed in October 1926 (CH120848). The new design featured a clutch which disengaged the stem when being screwed down.

All these early Oyster cases with wire lugs were made by casemaker C. R. Spillmann in La-Chaux-de-Fonds. They were the go-to casemaker for many later Rolex watches, especially chronographs such as vintage Daytonas. They also produced for other brands such as Omega (Speedmaster).

It is interesting to note that the Perregaux and Perret patent for the screw-down crown (CH119948) was first transferred to C. R. Spillmann on July 19, 1926, and only five days later on July 24, 1926, to Hans Wilsdorf. The patent for the Oyster case was filed on September 21, 1926. C. R. Spillmann was involved from the very beginning in the creation of the Oyster waterproof case and it stands to reason that they were the actual designers of the case.

In the 1930s, Rolex developed a new streamlined Oyster case design in collaboration with case maker Robert Meylan, featuring solid lugs and a simplified construction. The original 3-piece Oyster case construction with wire lugs, however, lived on in the diving tool watches made by Rolex for the famous military divers of the secret Italian Navy unit Decima Flottiglia MAS and distributed through Italian Rolex retailer G. Panerai & Figlio who equipped the watches with their own Radiomir dials.

With Rolex markings everywhere, it cannot be denied that these watches were made by Rolex.

There seems to be no reference to this important chapter of Rolex history in the authorized Submariner book, which is weird as these watches were the first professional diving tool watches in history. On the other hand, there are a few pages dedicated to the British movie ‘The Silent Enemy’, which recounts the adventures of Lieutenant-Commander Lionel ‘Buster’ Crabb in Gibraltar, famously hunting down Italian divers who were attempting to sabotage British battleships in the British Naval Base.

The only reason I can think of why the Italian side of the story was ignored is that Rolex does not want to a shine light on this rather dark episode involving Fascists and Nazis. You see, Hans Wilsdorf was German-born but became a British citizen during his time in London. His first wife Florence May Crotty was British. Supplying watches to the enemy was not a good look. In 1964, Rolex Director René-Paul Jeanneret mentioned the Panerai chapter in an interview but said Rolex had no idea where the watches were destined to:

“Before the last war, deep-sea diving had nothing to do with sport. It was practised for scientific and, on smaller scale, for military purposes.

The Italians in particular formed a diving corps that specialized in attacking warships under water. These divers became quite famous in 1940 and 1941 when they effected a series of raids against enemy vessels in the Mediterranean. As a matter of interest, they were equipped with ‘Oyster’ watches. We supplied these watches to a Swiss customer who reexported them elsewhere – we did not know to what destination and only learned it much later.”

As someone who has dedicated many years of his life to researching the fascinating history of Panerai, I find it very disappointing that Rolex does not own up to this part of its history.

Thoughts

This first-ever authorized Submariner book is a missed opportunity, but since it is one of many publications to come, things can get better. I hope this article will contribute to that. Sadly, this will probably be the only critical account of the book. Rolex is undoubtedly on the right track with opening their archives and sharing the origin stories of their watches. Collectors love this kind of information. However, this critique shows that archives can only take you so far. If the published information is false or full of errors, the whole effort comes across as half-baked. For CHF 140, I expect the topic to be taken serious.

Rolex watches are mass-produced products. It is the nature of marketing to exaggerate in order to generate that must-have feeling in consumers, but here we are also talking history and that is something that demands to be curated in a responsible fashion. As collecting watches is becoming as serious as collecting art, with anachronistic mechanical timepieces turning into a form of art themselves, the whole of the watch industry needs to face this new reality and start growing up. In 2024, with all the knowledge amassed by collectors, scholars and the watch community as a whole, disguising the marketing tales of the past as history is an absolute no-go. Nicholas Foulkes, who is the very definition of a whore-ological historian, has got some splaining to do.

I believe Rolex is looking to create real substance with this series of books, but neither the brand nor Foulkes seem to understand just how intricate and esoteric the world of Rolex collecting is. For a book talking about unlocking the deep, it remained quite shallow. Without the participation from astute insiders, it will be impossible to get it right. Nicholas Foulkes, who, horologically speaking, is a jack of all trades but master of none, is in way over his head. Get the man some help please. As the saying goes, if a job is worth doing, it is worth doing right. If you thought the Submariner is a complicated topic, wait until we get to the Daytona with a myriad of dial variations. Also, let’s talk Explorer. Is Rolex still going to use Jedi mind tricks to suggest having reached the summit of Everest in 1953? I bet with a historian as unprincipled as Foulkes, they probably would.

Thank you for your interest.

Special thanks to my friend @young.brando for providing excerpts from the book.

“Also, let’s talk Explorer. Is Rolex still going to use Jedi mind tricks to suggest having reached the summit of Everest in 1953? I bet with a historian as unprincipled as Foukles, they would.”

Hurrah for that final blast. And let’s hear it for Smiths, the plucky little English underdog whose watch did indeed go all the way to the summit with Sir Ed, who left his Rolex “behind in the comparative safety of the Base Camp” (letter to The Horological Journal, November 1953.) And Smiths made their movements entirely in-house (even the jewels and the oils) at a time when Rolex, well, didn’t.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Great article – thank you so much 👍👌👏! Why Rolex chose to publish such a fairy-tale book is beyond me. My guess is that they can simply come up with any claim and get away with it 🤪.

LikeLiked by 3 people

As a watch lover, I found it incredulous that the book was not better edited to correct blatant inaccuracies. Excellent review that I found both enlightening and worrying !

LikeLiked by 2 people

I haven’t had the chance to read Foulkes’ new book, so I can’t comment on it. However, I can confidently say that there is nothing inaccurate in your writing. As the saying goes, verum et nihil nisi verum—’the truth and nothing but the truth.’

LikeLiked by 2 people

Absolutely incredible job as always. I was waiting for you to tell the story of the first waterproof watch which is not Rolex at all (coming from someone that owns a 1929 Oyster).

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great research as usual!

Thanks for all your work!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much again Jose for your marvelous work of research and for sharing it !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jose, U da best! Legend!

LikeLike

I’ve always wondered how Perregaux and Perret succeeded in obtaining a patent for the screw down crown when there were already existing patents for the idea ?

Ezra Fitch in 1881

Almon Twing in 1881

Alcide Droz & Fils 1883

Aaron Lufkin Dennison in 1915

LikeLike

Great article !I wish rolex contact insiders like you and publish a real reference book for collectors. Maybe a 2nd edition revised by Perez? I would buy that !

LikeLike

When I buy a book I expect it to be error -free; especially when the book cost £110 with postage!

LikeLike